Michelangelo Buonarroti (Caprese, March 6, 1475-Rome, February 18, 1564), known in English as Michelangelo, was an Italian Renaissance architect, sculptor and painter, considered one of the greatest artists in history for his sculptures, paintings and architectural work.

He developed his artistic work for over seventy years between Florence and Rome, where his great patrons, the Medici family of Florence and the various Roman popes, lived.

He was the first Western artist of whom two biographies were published during his lifetime: Le vite de' più eccellenti pittori, scultori e architettori, by Giorgio Vasari, published in 1550 in its first edition, in which he was the only living artist included, and Vita de Michelangelo Buonarroti, written in 1553 by Ascanio Condivi, painter and disciple of Michelangelo, which includes the data provided by Buonarroti himself.

He was greatly admired by his contemporaries, who called him the Divine. Benedetto Varchi, on February 12, 1560, sent him a letter on behalf of all Florentines telling him:

... this whole city submissively desires to be able to see and honor you both near and far.... Your Excellency would do us a great favor if you would honor your homeland with your presence.

-Tolnay (1978, p. 14)

He triumphed in all the arts in which he worked, characterized by his perfectionism.a Sculpture, as he had declared, was his favorite and the first to which he devoted himself; then painting, almost as an imposition by Pope Julius II, and which took the form of an exceptional work, the vault of the Sistine Chapel; and already in his last years, he carried out architectural projects.

He was the author of numerous works, of which between 40 and 50 sculptures, 4 paintings, several dozen drawings and the frescoes of the Sistine Chapel and the Pauline Chapel are still preserved today.

Biography of Michelangelo

Family

He was born on March 6, 1475, in Caprese, a Tuscan village near Arezzo.5 He was the second of five sons of Ludovico di Leonardo Buonarroti di Simoni and Francesca di Neri del Miniato di Siena. His mother died in 1481, when Michelangelo was six years old. The Buonarroti Simoni family had lived in Florence for over three hundred years and had belonged to the Guelph party; many of them had held public office.

Economic decline began with the artist's grandfather, and his father, who had failed to maintain the family's social position, lived on occasional government jobs, such as that of corregidor of Caprese at the time Michelangelo was born.

They returned to Florence, where they lived on a small income from a marble quarry and a small estate they owned in Settignano, where Michelangelo had lived during his mother's long illness and death; there he was left in the care of a stonecutter's family.

His father had him study grammar in Florence with the master Francesco da Urbino. Michelangelo wanted to be an artist, and when he told his father that he wanted to follow the path of art, they had many discussions, since at that time it was a little recognized profession. Ludovico di Leonardo considered that such work was not worthy of the prestige of his lineage.

Thanks to his firm decision, and despite his youth, he managed to convince him to let him follow his great artistic inclination, which, according to Michelangelo, came from the wet nurse he had had, the wife of a stonecutter. Of her he commented: "Together with the milk of my wet nurse I also sucked the scarps and hammers with which I later sculpted my figures".

She maintained good family relations throughout her life. When his older brother, Leonardo, became a Dominican monk in Pisa, he assumed responsibility for the management of the family. He took care of the Buonarroti estate and expanded it with the purchase of houses and land, as well as arranging the marriage of his nephews Francesca and Leonardo to good families in Florence.

Michelangelo's Apprenticeship

From a very young age he manifested his artistic gifts for sculpture, a discipline in which he began to excel. In April 1488, at the age of twelve and thanks to the advice of Francesco Granacci, another young man who was dedicated to painting, he entered the workshop of the famous Ghirlandaio (Domenico and Davide); his family and the Ghirlandaio's entered into a three-year study contract:

1488. I, Ludovico di Lionardo Buonarota, on this first day of April, enroll my son Michelangelo as apprentice to Domenico and Davide di Tomaso di Currado, for the next three years, under the following conditions: That the said Michelangelo is to remain for the time agreed upon with the aforementioned to learn and practice the art of painting and that he is to obey their instructions, and that the said Domenico and Davide are to pay him in these years the sum of twenty-four florins of exact weight: six during the first year, eight the second year and ten the third year, in total a sum of ninety-six lire.

-Hodson (2000, p. 14)

There he remained as an apprentice for a year, after which, under the tutelage of Bertoldo di Giovanni, he began to frequent the garden of San Marco dei Medici, where he studied the ancient sculptures gathered there.

His first artistic works aroused the admiration of Lorenzo the Magnificent, who welcomed him to his Palazzo on the Via Longa, where Michelangelo was to meet Angelo Poliziano and other humanists of the Medici circle, such as Giovanni Pico della Mirandola and Marsilio Ficino.

These relationships brought him into contact with the idealistic theories of Plato, ideas that eventually became one of the fundamental pillars of his life and which he expressed both in his plastic works and in his poetic production.

According to Giorgio Vasari, one day, leaving the Medici garden - or, according to Benvenuto Cellini, the Brancacci chapel, where he and other students were learning to draw in front of Masaccio's frescoes - Pietro Torrigiano punched him and broke his nose; as a result, his nose remained flat all his life, as can be clearly seen in all his portraits.

Artistic career

After the death of Lorenzo the Magnificent in 1492, Michelangelo fled Florence and passed through Venice, later settling in Bologna. There he sculpted several works under the influence of the work of Jacopo della Quercia. But in 1496 he decided to leave for Rome, the city that was to see him triumph. There he began a decade of great artistic intensity, after which, at the age of thirty, he would be credited as a first-rate artist.

After the Bacus del Bargello (1496), he sculpted the Pietà of the Vatican at the age of twenty-three, and later he made the Tondo Pitti.

From the same period is the carton of The Battle of Cascina, now lost, painted for the Lordship of Florence, and the David, a masterpiece of sculpture, of great complexity due to the small width of the marble piece, which was placed in front of the palace of the Town Hall of Florence and became the expression of the supreme civic ideals of the Renaissance.

In March 1505, Julius II commissioned him to create his funeral monument: Michelangelo designed a monumental architectural and sculptural complex in which, more than the prestige of the pontiff, the triumph of the Church was praised. The sculptor, enthusiastic about this work, remained in Carrara for eight months to personally select and direct the extraction of the necessary marble.

When he returned to Rome, the pope had put aside the mausoleum project, absorbed as he was with Bramante's renovation of St. Peter's Basilica. Michelangelo, disgruntled, left Rome for Florence, but at the end of November 1506, after numerous calls from the pontiff-who even threatened him with excommunication-he met with him in Bologna.

In May 1508, he agreed to direct the decoration of the vault of the Sistine Chapel, whose frescoes he completed four years later, after a solitary and tenacious work.

In this work he devised a grandiose painted architectural structure, inspired by the actual shape of the vault. In the general biblical theme of the vault, Michelangelo interposed a neoplatonic interpretation of Genesis and shaped a type of interpretation of the images that would become a symbol of Renaissance art.

After the death of Julius II, in May 1513, the artist made a second attempt to continue the work on the pontiff's mausoleum. For this purpose he sculpted the two figures of the Slaves and the Moses, which reflect a tormented energy, Michelangelo's terribilitá. But this second attempt did not succeed either.

Finally, after the death of Bramante (1514) and Raphael Sanzio (1520), Michelangelo gained the full confidence of the papacy.

The great delay with which Michelangelo obtained official recognition in Rome must be attributed to the heterodoxy of his style. He lacked what Vitruvius called decòrum, that is, respect for tradition.

In 1516, commissioned by Leo X, he began the project for the façade of the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence, a work that in 1520 he had to abandon with great bitterness. Numerous drawings and a wooden model of the original project have survived. From 1520 to 1530, Michelangelo worked in Florence and built the New Sacristy of San Lorenzo and the Laurentian Library, especially its staircase.

After the sack of Rome (1527) and the expulsion of the Medici from Florence, Michelangelo took part, as a purely anecdotal fact, in the government of the new Florentine Republic, of which he was appointed "governor and procurator general of the manufacture and fortification of the walls", and participated in the defense of the city besieged by the papal troops.

In 1530, after the fall of the Republic, the pardon of Clement VII saved him from the vengeance of the Medici supporters. From that year on he resumed work on the New Sacristy and the tomb of Julius II.

In 1534, finding himself displeased with the new political situation that had been established in Florence, he left the city and settled in Rome, where he accepted a commission from Clement VII to work on the altar of the Sistine Chapel and where, between 1536 and 1541, he executed the magnificent Last Judgment.

Until 1550 he was doing works for the tomb of Julius II, and the frescoes of the Pauline Chapel (The Conversion of St. Paul and Crucifixion of St. Peter).

Love life of Michelangelo

Michelangelo sought to internalize the Neoplatonic theories of love, making great efforts to achieve an emotional balance that he rarely achieved. His natural inclination for matter, for physical forms -he was above all a sculptor of bodies-, together with his fascination for everything young and vigorous, emblems of classical beauty, led him to opt for human beauty and the most sensual love until very late in his life.

This conflict with which the artist lived his carnal desire, also surfaced in the confrontation with a supposed homosexuality.

The artist had relationships with several young men, such as Cecchino Bracci, for whom he felt great affection. When Bracci died in 1543, Michelangelo designed his tomb in the church of Santa Maria in Aracoeli in Rome, and commissioned his disciple Urbino to do it.

Giovanni da Pistoia, a beautiful young man of letters, was also a close friend for a time, and some scholars suggest that he had a love affair with Michelangelo at the time he began to paint the vault of the Sistine Chapel; this relationship is reflected in some very passionate sonnets that Giovanni dedicated to him.

Tommaso Cavalieri

On a trip to Rome in 1532, he met the young Tommaso Cavalieri, a patrician of uncommon intelligence and a lover of the arts who left a vivid impression on the artist. Shortly after meeting him, he sent him a letter in which he confessed: "Heaven did well to prevent me from fully understanding your beauty.... If at my age I am not yet fully consumed, it is because the encounter with you, sir, was very brief. "

It is necessary to remember that the Platonic Academy of Florence wanted to imitate the Greek city of Pericles. This cultural association of a philosophical nature promoted intellectual dialogue and friendship among men in an idealistic tone, similar to the relationship between Socrates and his disciples in ancient Greece.

It is within this context that Michelangelo's psychology, taste and art can be understood. The artist believed that the beauty of man was superior to that of woman and, therefore, the love he felt for Tommaso was a way for him to surrender to "Platonic beauty. "

Tommaso Cavalieri was a boy of 22; from a well-to-do family, fond of art, as he painted and sculpted. Varchi said of him that he had "a reserved and modest temperament and an incomparable beauty"; he was, therefore, very attractive as well as witty.

At their first meeting, he already made a deep impression on Michelangelo, and as time went by the relationship developed into a great friendship, with a passion and fidelity that lasted until his death.

Michelangelo, on the other hand, was a man of 57, who was at the zenith of his fame; he had the support of the various popes and Tommaso admired him deeply.

It seems that the friendship took some time to develop, but when it was consolidated it became very deep to the point that Cavalieri, already married and with children, was his disciple and friend during Michelangelo's lifetime and assisted him at the hour of his death.

Vittoria Colonna

Vittoria Colonna was a descendant of a noble family, and one of the most notable women of Renaissance Italy. As a young woman she married Fernando de Avalos, Marquis of Pescara, a powerful man who died in the battle of Pavia while fighting on the Spanish side in the service of Charles I.

After her husband's death she retired from court life and devoted herself to religious practice. She joined the reformist group of Erasmist and evangelical roots gathered in Naples around Juan de Valdes.

In the convent of San Silvestro in Capite in Rome in 1536, the artist met this lady and from the beginning there was a mutual empathy, perhaps because they both had the same religious concerns and both were great fans of poetry.

According to Ascanio Condivi, Michelangelo "was in love with her divine spirit" and, as he was a great admirer of Dante, she represented what the character of Beatrice meant to the poet. This is clear from reading the poems dedicated to Vittoria, as well as the drawings and verses she gave him, all of which had religious themes: a Pietà, a Crucifixion and a Holy Family.

Vittoria died in 1547, a fact that left Michelangelo in the deepest sorrow. As he himself confessed to Ascanio Condivi: "There had been no deeper sorrow in this world than to have let her depart from this life without having kissed her forehead, nor her face, as he kissed her hand when he went to see her on her deathbed. "

Michelangelo's Last years

During the last twenty years of his life, Michelangelo devoted himself above all to architectural works: he directed the works of the Laurenziana Library in Florence and, in Rome, the remodeling of the Capitoline Square, the Sforza Chapel of Santa Maria Maggiore, the completion of the Farnese Palace and, above all, the completion of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican.

From this period are the last sculptures such as the Palestrina Pietà and the Rondanini Pietà, as well as numerous drawings and poems of religious inspiration.

The project for the Vatican basilica, on which he worked during the last years of his life, simplifies the project conceived by Bramante, although it maintains the structure with a Greek cross plan and the great dome. Michelangelo created spaces, functions that encompass the main elements, especially the dome, the main element of the whole.

He died in Rome in 1564, before the completion of his work, at the age of eighty-eight, accompanied by his secretary Daniele da Volterra and his faithful friend Tommaso Cavalieri; he had written that he wished to be buried in Florence. He made a will in the presence of his physician Federigo Donati, "leaving his soul in the hands of God, his body to the earth and his goods to the next of kin".

His nephew Leonardo was in charge of carrying out this last will of the great artist, and on March 10, 1564 he was buried in the sacristy of the church of Santa Croce; the funerary monument was designed by Giorgio Vasari in 1570. A solemn funeral was held on July 14; it was Vasari who described these funerals, which were attended, in addition to himself, by Benvenuto Cellini, Bartolomeo Ammannati and Bronzino.

Sculptural work of Michelangelo

Early works

Between 1490 and 1492, he made his first drawings, studies on the Gothic frescoes of Masaccio and Giotto; among the first sculptures it is believed that he made a copy of a Faun's Head, now disappeared.

The first reliefs were the Madonna of the Staircase and The Battle of the Centaurs, preserved in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence, in which there is already a clear definition of his style. He shows himself as the clear heir of Florentine art of the 14th and 15th centuries, while establishing a more direct link with classical art.

In the marble relief of The Battle of the Centaurs, he was inspired by Book XII of Ovid's Metamorphoses and shows the naked bodies in the heat of combat, intertwined in full tension, anticipating the serpentine rhythms so often used by Michelangelo in his sculptural groups. Ascanio Condivi, in his biography of the artist, reported having heard him say:

... that when he saw it again, he realized to what extent he had behaved badly with nature by not following his inclination in the art of sculpture, and he judged, by that work, all that he could have done.

-Pijoan (1966, p. 206)

Another sculpture of the same period (around 1490) is also a relief with a Marian theme, the Madonna of the staircase, which presents a certain scheme similar to those of Donatello, but in which all the energy of Michelangelo's sculpture is shown, both in the way of the treatment of the planes of the figure and in its so vigorous contour and the anatomy of the child Jesus with the insinuation of the contrapposto.

After the death in 1492 of Lorenzo the Magnificent, and on his own initiative, he made the sculpture of a marble Hercules in his father's house; he chose this subject because Hercules was, since the thirteenth century, one of the patrons of Florence.

The statue was bought by the Strozzi family, who sold it to Giovan Battista Palla, from whom it was acquired by King Henry III of France and placed in a garden at Fontainebleau, where Rubens made a drawing before his disappearance in 1713. All that remains is the drawing and a sketch preserved in the Buonarroti house.

He then stayed for a time at the convent of Santo Spirito, where he carried out anatomical studies with corpses from the convent's hospital. For the prior Niccolò di Giovanni di Lapo Bichiellini executed a Crucifix in polychrome wood, where he resolved the naked body of Christ, like that of an adolescent, without emphasizing the musculature, although the face looks like that of an adult, with a disproportionate size with respect to the body;

the polychrome is painted with subdued colors and with very soft lines of blood, which achieve a perfect union with the carving of the sculpture. It was considered lost during the French domination, until its recovery in 1962, in the same convent, covered with a thick layer of paint that showed it practically unrecognizable.

The Florence ruled by Piero de' Medici, son of Lorenzo the Magnificent, did not satisfy Michelangelo, who traveled to Bologna in October 1494, where he discovered the relief panels of the door of San Petronio by Jacopo della Quercia, a late Gothic master sculptor, whose style includes the wide folds of the vestments and the pathos of his figures.

He was commissioned by Francesco Aldovrandi to create three sculptures to complete the tomb of the founder of the convent of San Domenico Maggiore, called the Ark of St. Dominic, for which he sculpted a kneeling candelabra-bearing Angel, which forms a pair with another by Niccolò dell'Arca, as well as a St. Proculus and a St. Petronius, which are now kept in the Basilica of St. Dominic in Bologna.

Once these works were finished, in a little more than a year, he returned to Florence.

Around this time, the Dominican Girolamo Savonarola called for a theocratic republic, and his criticisms led to the expulsion of the Medici from Florence in 1495. Savonarola called for the return of sacred art and the destruction of pagan art.

All these sermons caused great doubts in Michelangelo, between faith and knowledge, between body and spirit, and made him wonder if beauty was sin and if, as the monk said, the presence of the human body had to be eliminated from art.

In his preaching against papal absolutism, on February 7, 1497 he organized a great bonfire (Bonfire of the Vanities) in the square of the Signoria, where he ordered the burning of images, jewelry, musical instruments and also books by Boccaccio and Petrarca; as a result of this action he was excommunicated by Pope Alexander VI.

The following year Savonarola repeated the action, for which he was finally arrested and burned at the stake on May 23, 1498.

Back in Florence, between 1495 and 1496, he carved two works: a St. John, sculpted for Lorenzo de Pierfrancesco de Medici, and a Sleeping Cupid.

The San Juanito, after its restoration completed in 2013, has been identified with the sculpture kept in the Chapel of the Savior of Úbeda, destroyed in 1936, confirming the theory put forward by Manuel Gómez-Moreno as early as 1931 of the donation of the work to Francisco de los Cobos, Secretary of State of Charles I, by Cosimo I de Medici.

Previously there had also been speculation that it was a sculpture in the Kaiser Friedrich Museum in Berlin, or another one on the door of the sacristy of San Giovanni dei Fiorentini in Rome. It is explained that the Sleeping Cupid, made according to the most classical Hellenistic model, was buried to give it an antique patina and sell it to the Cardinal of San Giorgio, Raffaele Riario, as an authentic piece, without Michelangelo's knowledge.

Later, it was bought by Cesare Borgia and finally given as a gift to Isabella d'Este; later, in 1632, it was sent to England as a present for King Charles I, after which it was lost track of.

First stay in Rome

His departure for Rome took place on June 20, 1496. The first work he made was a Bacchus with a satyr of natural measure, with great resemblance to a classical statue, and commissioned by Cardinal Riario, which, being rejected, was acquired by the banker Jacopo Galli.

It was later purchased by Francesco I de' Medici and is now preserved in the Bargello Museum in Florence. Ascanio Condivi was the first to compare the statue to the works of classical antiquity:

... this work, for its form and manner, in each of its parts, corresponds to the description of the ancient writers; its festive aspect: the eyes, furtive looking and full of lasciviousness, like those of those who are excessively given to the pleasures of wine. He holds a cup in his right hand, as one who is about to drink, and looks at it lovingly, feeling the pleasure of the liquor he invented; for this reason he is depicted crowned with a braid of vine leaves.... With his left hand he holds a bunch of grapes, which delights a lively and cheerful little satyr at his feet.

This is clearly Michelangelo's first great masterpiece, showing the constant feature of sexuality in his sculpture and symbolizing the spirit of classical hedonism that Savonarola and his followers were determined to suppress from Florence.

At the same time that he was making the Bacchus, on commission from Jacopo Galli, he sculpted a standing Cupid, which later came to belong to the Medici collection and is now missing.

Through said collector Galli, in 1497 he received from the French cardinal Jean Bilhères de Lagraulas the commission for a Pietà as a monument for his mausoleum in the chapel of Saint Petronila in the ancient basilica of Saint Peter's, and which was later installed in Bramante's new construction.

The originality with which Michelangelo treated this piece is noticeable in the break with the dramatism with which this iconography was treated until then, which always showed the great pain of the mother with the dead child in her arms.

Michelangelo, however, created a serene, concentrated and extremely young Madonna, and a Christ who seems to be asleep and with no signs on his body of having suffered any martyrdom: the artist displaced any kind of painful vision in order to make the spectator reflect before the great moment of death. It is the only work by Michelangelo that he signed: he did so on the ribbon that crosses the Virgin's chest:

An ivory Crucifix, dated around the period 1496-1497, has recently been attributed to Michelangelo. This image is found in the monastery of Montserrat and represents according to the historian Anscari M. Mundó, the last agony of Christ, with the head tilted to the right, the mouth open and the eyes almost closed;

he is crowned with thorns, young body with open arms, naked, protected with a cloth of purity folded with irregular folds that holds a double cord. It presents a good anatomy very realistic and shows the wound to the right of the ribs.

It measures 58.5 cm in height. It is believed to have been acquired by Abbot Marcet in 1920 during a trip to Rome, believing it to be a work by Ghiberti. Since 1958 it has been on the high altar of the Abbey of Montserrat.

Return to Tuscany

He returned to Florence in the spring of 1501, after five years away from Tuscany. With Savonarola dead, a new republic had been declared in Florence, governed by a gonfaloniere, Piero Soderini, an admirer of Michelangelo, who gave him one of the most important commissions of his life: the David.

He put at his disposal a large block of abandoned marble that had been started by Agostino di Duccio in 1464 and was located in Santa Maria del Fiore. Vasari explains that when he received the commission, the ruler thought the block was unusable and asked him to do his best to shape it.

Michelangelo made a wax model and began to sculpt in the same place where the block was located without letting anyone see his work for more than two and a half years, which was the time it took him to finish it.

He made the representation of the sculpture in the phase before the fight with Goliath, with a look charged with uncertainty and with the symbolic personification of David defending the city of Florence against his enemies.

The Florentines saw David as a victorious symbol of democracy. This work shows all the knowledge and studies of the human body achieved by Michelangelo up to that date. The technique employed was described thus by Benvenuto Cellini:

'The best method ever employed by Michelangelo; after having drawn the main perspective on the block, he began to tear off the marble on one side as if he intended to work a relief and thus, step by step, to bring out the complete figure.

-Hodson (2000, p. 42)

As soon as it was finished, on the advice of a commission formed by the artists Francesco Granacci, Filippino Lippi, Sandro Botticelli, Giuliano da Sangallo, Andrea Sansovino, Leonardo da Vinci and Pietro Perugino, among others, it was decided to place it in the Piazza della Signoria in front of the Palazzo Vecchio.

From there, in 1873, it was transferred for better conservation to the museum of the Galleria dell'Accademia, while a copy, also in marble, was placed in the square.

Around the same time, he was working on the Tondo Taddei, a marble relief 109 cm in diameter showing the Madonna and Child and St. John the Baptist, also a child, placed on the left holding a bird in his hands. The figure of Jesus and the upper part of the Virgin are finished, but the rest is not.

The relief was acquired by Taddeo Taddei, protector of the painter Raffaello Sanzio, and is now in the Royal Academy of Arts in London. Another high relief, the Tondo Pitti, also in marble, begun for Bartolomeo Pitti, shows the Virgin seated with Jesus leaning on an open book above his mother's knees. It has been in the museum of the Bargello since 1873; like the previous one it is unfinished.

In 1502, the Lordship of Florence commissioned a bronze David for Pierre de Rohan, Marshal of Gié, who had passed through Italy with the retinue of Charles VIII of France and had made a request for an image of the David. Michelangelo began to design it, but because of his tardiness had to resort to casting by the sculptor Benedetto da Rovezzano to finish the work. Subsequently the trace has been lost.

Around 1503 he made, commissioned by some Flemish merchants, the Mouscron, a Virgin and Child for a chapel in the church of Our Lady of Bruges.

Although the movement of the clothes can be appreciated as in the Vatican Pietà, the result is different, especially because of the verticality of the sculpture. It is depicted in a moment of abandonment, where the Virgin's right hand seems to have only the strength to keep the book from falling and the left hand is gently holding the infant Jesus, in contrast to the vitality of movement shown by the Child.

On April 24, 1503, the sculptor signed a contract with the representatives of the wool guild (Arte della Lana), by virtue of which he undertook to make twelve images of the apostles for Santa Maria del Fiore. He only began the one of St. Matthew, a marble work 261 cm high, which he left unfinished and which is in the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence.

For the Piccolomini chapel in the cathedral of Siena, he made between 1503 and 1504, four images, those of St. Paul, St. Peter, St. Pius and St. Gregory (the latter of uncertain authorship), with a great richness of folds in the vestments and a good balance between shadows and lights. On the back they are only sketched, since they were sculpted to be placed inside some niches of the altar made by Andrea Bregno between 1483 and 1485.

The tragedy of the sepulcher

In 1505 he was called to Rome by Pope Julius II to propose the construction of the papal tomb to be placed under the dome of St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican. The whole succession of events during the forty years it took for the realization of the tomb was called by Ascanio Condivi "the tragedy of the sepulcher", as the whole parade of misfortunes of this work will be known from then on.

The artist considered the tomb of Julius II the great work of his life. The first project presented was an isolated monument with a rectangular plan and a three-story stepped pyramidal shape, with a large number of sculptural figures. Once the pope gave the go-ahead, Michelangelo spent about eight months in the quarries of Carrara choosing the marble blocks for the work.

At Bramante's suggestion, Julius II changed his mind and asked the sculptor to stop work on the mausoleum and start painting the vault of the Sistine Chapel.

On April 17, 1506 Michelangelo, disgruntled, left Rome and went to Florence, but at the end of November, after numerous calls from the pontiff, who threatened to excommunicate him, he met with him in Bologna.

The pope assigned him a job in this city: a colossal bronze statue of Pope Julius, which was delivered in February 1508, and was installed on the facade of the basilica of San Petronio. This sculpture was destroyed in December 1511 by Bolognese rebels.

In 1513, when the painting of the vault of the Sistine Chapel was finished and Michelangelo thought he could sculpt the marbles of the sepulcher, Pope Julius II died and the execution was postponed for two more decades.

Six different projects were carried out and finally in 1542 the tomb was built as an altarpiece with only seven statues, and it was installed in the church of San Pietro in Vincoli and not in the Vatican basilica.

The great sculpture of the tomb is the figure of Moses, the only one of those conceived in the first project that reached the end of the work. The colossal statue, with the terribilitá of his gaze, demonstrates extreme dynamism.

It is placed in the center of the lower part, so that it becomes the center of attention of the final project, with the statues of Rachel and Leah placed one on each side. The rest of the monument was made by his assistants.

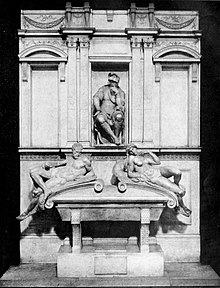

Around 1520, Pope Clement VII commissioned him to design the tombs of his relatives Lorenzo the Magnificent, father of Leo X, and his brother Julian (father of Clement VII), and two more tombs for other members of the family: Julian II and Lorenzo II, in the sacristy of the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence.

The pope proposed four tombs, one on each wall of the square floor plan of the sacristy, a Madonna and Child and the images of Saints Cosmas and Damian, which were to be placed in the center of the room on an altar.

Once the project was approved, it was not begun until 1524, when the blocks of Carrara marble arrived. Michelangelo applied the sculptures next to the architecture of the walls; all the moldings and cornices fulfill the function of shadow and light and are composed of a curvilinear sarcophagus on which there are two statues with the symbolism of time.

On the one of Lorenzo, the Twilight, with the outlines of an aging man but still in full possession of his strength, which has a symmetrical attitude to the Aurora, which is on the right and above both, inside a niche, the statue of Lorenzo, nephew of Leo X, whose head is covered with the helmet of the Roman generals; his attitude of meditation made him immediately known by the name of "the thinker. "

Above Julian's tomb are the allegories of the Night, which despite symbolizing death announces supreme peace, and the Day, which shows the unfinished head of a man, this representation of an old person being very singular. It symbolizes the image of the tiredness of starting a day without wishing it.

Above them the statue of Julian, brother of Leo X, with a great resemblance to the sculpture of Moses in the tomb of Julius II; despite the armor with which he dressed him, the body of a young athlete can be appreciated.

In short, the portraits of these personages of the Medici house are more spiritual than physical, the character is shown rather than the material appearance. When the sculptor was told that they bore little resemblance to real people, he replied, "And who will notice in ten centuries' time? "

Michelangelo also realized the sculpture of the Madonna and Child, which is a symbol of eternal life and is flanked by the statues of St. Cosmas and St. Damian, protectors of the Medici, executed on a model by Buonarroti, respectively by Giovanni Angelo Montorsoli and Raffaello da Montelupo. Lorenzo the Magnificent (Michelangelo's first patron) and his brother Julian are buried here.

These last tombs were left incomplete, as were the sculptures representing the rivers, which were to be placed in the lower part of the other tombs already completed, due to Michelangelo's definitive departure to Rome in 1534 because of the political situation in Florence.

For these tombs he also sculpted a Young Man squatting in marble, representing a naked young man, bent over himself; surely he wanted to represent the souls of the "unborn". It was one of the sculptures that remained in the sacristy in 1534, when Michelangelo traveled to Rome. This statue is in the Hermitage Museum in St. Petersburg.

Michelangelo's Other sculptural works

A new version of the Christ of the Minerva, made for Metello Vari, follows the one begun in 1514, which was abandoned because of the defects of the marble; the contract for the sculpture specifies that it will be "a marble statue of a Christ, of natural size, nude, with a cross between the arms and the symbols of the passion, in the position that Michelangelo deems most appropriate".

The work was sent to Rome in 1521, where it was finished by his assistant Pietro Urbano, who changed the line and gave it a very different finish from that of Michelangelo, who had initially treated it as a young adolescent athlete and was accustomed to leaving his sculptures with voluntarily unfinished planes. It was placed in the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva in Rome.

Around 1530, Baccio Valori, commissioner to Pope Clement VII and the new governor of Florence, commissioned him to make a statue of Apollo or David. It is believed that Michelangelo was initially inclined toward the execution of a David, as the round form below the right foot is considered a sketch for making the head of Goliath.

The figure, is definitely dedicated to Apollo, with the image of the body evoking the form of a woman, treated as Narcissus in love with himself; it shows a clear contrapposto. It is in the Florentine museum of the Bargello.

The bust of Brutus was made around 1539 in Rome and is also in the Bargello. It was commissioned by Cardinal Niccolò Ridolfi, executed in an antique style, similar to the Roman busts of the first and second centuries of our era; it was finished by his pupil Tiberio Calcagni, especially in the part of the vestments.

It has a height of 74 cm without the pedestal. Giorgio Vasari was the first to relate its iconography to classical antiquity and Tolnay noted reminiscences of a Roman bust of Caracalla in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

The Florentine Pieta, so called because it is in the Duomo of Florence, is believed to have been begun from 1550. According to Vasari and Condivi, Michelangelo designed this sculptural group with the idea that he would be buried at his feet, inside the basilica of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.

Later, he abandoned this desire to be buried in Florence, and also because of the opportunity of its sale, in 1561, to Francesco Bandini, who placed the sculpture in the Roman gardens of Montecavallo, where it remained until its transfer to the basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence by Cosimo III in 1674; finally in 1722 it was placed in Santa Maria del Fiore and since 1960 it has been in the cathedral museum.

The sculptural group of the Florentine Pieta consists of four characters: the dead Christ who is supported by the Virgin, Mary Magdalene and Nicodemus, the features of which are a self-portrait by Michelangelo.

The structure is pyramidal, with Nicodemus as the vertex, and the Christ is shown as a serpentine figure typical of Mannerism. In 1555, it is not known exactly, whether by accident or because the work did not seem right to the author, he broke it into several pieces. Vasari explains:

Perhaps because the stone was hard and full of emery and the chisel drew sparks, or perhaps because of his severe self-criticism, he was never happy with anything he did .... Tiberio Calcagni asked him why he had broken the Pietà and thus lost all his wonderful efforts. Michelangelo replied that one of the reasons was because his servant had been pestering him with his daily sermons to finish it, and also because a piece of the Madonna's arm had broken off. And all this he said, as well as other misfortunes, such as that he had discovered a fissure in the marble, having made him hate the work, he had lost patience and had broken it.

Later, the Florentine Pietà was restored by Tiberio Calcagni, although some damage can still be seen on the arm and leg of Christ.

Another work on the same theme and made during the same period (1556) is the Palestrina Pietà, a sculptural group with Christ, the Virgin and Mary Magdalene, two and a half meters high.

Michelangelo used for its elaboration a fragment of a Roman construction; on the back a piece of ancient decoration of a Roman architrave can be seen. It is unfinished and, after being in the chapel of the Palazzo Barberini in Palestrina, it can now be seen in the Galleria dell'Accademia in Florence.

Michelangelo also began the Rondanini Pietà, which would be the last sculpture on which he would work until the eve of his death. The religiosity shown in these last sculptures is the result of an internal crisis of the author. The images of the Rondanini Pietà are elongated and both Christ and the Virgin are completely united as if they were a single body, a dramatic frontality of medieval origin can be appreciated.

He left it, unfinished, as a legacy, in 1561, to his faithful servant Antonio del Franzese. It was kept for centuries in the courtyard of the Palazzo Rondanini and in 1952 was acquired by the Municipality of Milan and placed for exhibition in the civic center of the Sforza's Sforzesco Castle.

Of all his sculptures, the Rondanini Pietà is the most tragic and mysterious. In the inventory of his house in Rome, it is referred to as "another statue begun of a Christ with another figure above, together, sketched and unfinished. "

Pictorial work of Michelangelo

The Torment of St. Anthony

The first painting attributed to Michelangelo, when he was twelve years old, was the Torment of St. Anthony.

The painting, cited by the artist's early biographers, was a variant copy of a well-known engraving by the German Martin Schongauer. A painting of this subject was auctioned as a work "from the workshop of Ghirlandaio," acquired by an American dealer and subjected to various analyses at the Metropolitan Museum in New York in 2009.

Several experts on Michelangelo's work identify it as the painting that the Florentine made during his apprenticeship with Ghirlandaio, although there are doubts about this. Finally, it was acquired by the Kimbell Art Museum in the United States.

Holy Burial

Until the recent discovery of The Temptations of Saint Anthony, the Holy Burial and the Madonna of Manchester were the first paintings attributed to Michelangelo. The Holy Burial is an unfinished tempera panel, dated around 1500-1501, in the National Gallery in London.

Thanks to documents published in 1980, it is known that during his stay in Rome he was commissioned to make an altarpiece for the church of Sant'Agostino in that city and that the artist returned the payment received on account, since he had not been able to finish it due to his return to Florence in 1501.

This panel, which for many years has been in doubt as to whether it belonged to Michelangelo, has finally been recognized as his work. The figures of Christ and St. John show the most strength, and their composition is superb; the figure of Joseph of Arimathea, situated behind Jesus Christ, bears a curious resemblance to that of St. Joseph in the Tondo Doni.

Tondo Doni

The Tondo Doni, also known as the Holy Family (1504-1505), is today in the Uffizi Gallery, Florence. This tempera painting, he painted for Agnolo Doni, as a wedding gift to his wife Maddalena Strozzi. In the foreground is the Madonna and Child and behind, St. Joseph, of grandiose proportions and dynamically articulated; the images are treated as sculptures within a circular arrangement of 120 cm in diameter and with a pyramidal composition of the main figures.

The base of the triangular line is the one marked by the legs of the kneeling Virgin, with her head turned to the right, where the Child is found, supported by Saint Joseph, with her body leaning to the left; this upper part of the painting, together with the line marked by the arms, denotes a spiral movement.

Separated by a balustrade are John the Baptist and a group of ignudi. This painting can be seen as the succession of the various epochs in the history of man: the ignudi would represent the pagan civilization, St. John and St. Joseph the Mosaic era, and the Virgin and Child the era of Redemption, through the incarnation of Jesus.

This interpretation is also supported by the heads sculpted on the original cornice: two sibyls (representing the pagan age), two prophets (representing the Mosaic age) and the head of Christ (representing the era of redemption), with intermediate friezes of animals, satyr masks and the Strozzi emblem.

The artist demonstrated that with painting he was able to express himself with the same grandeur as in sculpture; the Tondo Doni, in fact, is considered the starting point for the birth of Mannerism.

Sistine Chapel vaulting

Between March and April 1508, the artist was commissioned by Julius II to decorate the vault of the Sistine Chapel; in May he accepted and completed the frescoes four years later, after a solitary and tenacious work. The pope's project was the representation of the twelve apostles, which Michelangelo changed for a much larger and more complex one.

He devised a grandiose painted architectural structure, inspired by the actual shape of the vault. To the general biblical theme of the vault, Michelangelo interposed a neoplatonic interpretation with the representation of nine scenes from Genesis, each surrounded by four naked young men (ignudi), together with twelve prophets and the sibyls.

A little lower down are the ancestors of Christ. All these scenes are masterfully differentiated by means of imitation architectures. These images became the very symbol of the art of the Renaissance.

He began work on May 10, 1508, refusing the collaboration of expert fresco painters; he also had the scaffolding put up by Bramante removed and new ones designed by him put up.

While working on his first fresco (The Flood), he had problems with the paint, the humidity altered the colors and the drawing, he had to turn to Giuliano da Sangallo for a solution and start over; Michelangelo learned by dint of suffering the fresco technique, since, according to Vasari, it was necessary:

... to complete the entire scene in a single day.... The work is executed on the still fresh lime, until the planned part is completed.... The colors applied on the wet wall produce an effect that is modified when it dries... What has been frescoed remains forever, but what has been retouched when dry can be removed with a damp sponge...

The surface painted in one day is called a "day"; the scene of The Creation of Adam, one of the most spectacular in the vault, was completed in sixteen days.

The artist was also under the strain of continual arguments with the pope, the rush to finish the painting, and the payments he did not receive. Finally, the great work of painting the vault was publicly presented on October 31, 1512.

Final Judgment

Commissioned by Pope Clement VII and later confirmed by Paul III, Michelangelo agreed to paint on the altar wall of the Sistine Chapel the Last Judgment, or Last Judgment, begun in 1536 and completed in 1541.

The theme is based on the Apocalypse of St. John. The central part is occupied by a Christ with an energetic gesture, who separates the righteous from the sinners, and at his side is his mother Mary, fearful because of the violent gesture of her Son.

Around him are the saints, easily recognizable since most of them show the attributes of their martyrdom, among which is Saint Bartholomew, who in his martyrdom was skinned; this saint has his own skin hanging in his hand, where one can recognize Michelangelo's self-portrait.

Just below is a group of angels with trumpets, announcers of the Judgment. All the scenes are surrounded by a multitude of characters, some on the right side of Christ, those who ascend to heaven, and on the left the damned who descend into darkness, some of whom are on top of Charon's boat, present in Dante's Divine Comedy.

In the semicircles of the upper part of the mural appear angels with the symbols of the Passion of Christ, on one side the cross where he died and on the other the column where he was scourged.

In spite of the admiration that this work awakened, there were also protests about the nudity and the characters' aptitudes, since they were considered immoral. The papal master of ceremonies, Biagio da Cesena, said that the painting was dishonest, but one of the most vocal critics against the nudes, arguing that "a bonfire should be made with the work", was Pietro Aretino.

In 1559, Daniele da Volterra was commissioned by Pope Paul IV to cover the "embarrassments" of the nude figures, for which he became known as il Braghettone; the painter died after two years, without having been able to complete his work.

After the restoration begun in 1980, the paintings look again as Michelangelo painted them.

Pauline Chapel

Once the Last Judgment was finished, Pope Paul III commissioned him to paint two large frescoes for the Pauline Chapel (built by Antonio da Sangallo the Younger), on which Michelangelo worked from 1542 to 1550: The Conversion of St. Paul and The Martyrdom of St. Peter.

There were several reasons that delayed the execution of these works, among them the fire of 1544, an illness of the artist that delayed the second fresco until 1546, as well as the deaths of his friends Luigi del Riccio in 1546 and later of Vittoria Colonna in 1549.

It seems that the first fresco he completed was The Conversion of St. Paul, which is the one most similar in style to the Last Judgment, especially for the image of St. Paul, head down with his arms pointing one to the earth and the other towards the clouds, reminiscent of the swirl of the chosen and the damned around Jesus at the Judgment.

In this fresco, the partition between the heavenly and the earthly world is also visible, with the contrast between the main object at the bottom: the horse looking to the right, and the top: Jesus Christ looking the other way.

This great dynamism is much more contained in the following fresco The Martyrdom of St. Peter, where we can appreciate the balanced compositional rhythm, as opposed to the disorder existing in The Conversion of St. Paul.

The main line, diagonally, is represented by the cross not yet raised, and the figures that describe a large semicircular arch near the center. Thanks to the movement of St. Peter's head, Michelangelo achieves the main focal point of the scene.

Michelangelo's Crucifixion

In 1540 Vittoria Colonna asked him for a small painting of the Crucifixion to help her in her private prayers. After presenting her with several sketches, which are preserved in the British Museum and the Louvre, the artist gladly painted a small Calvary, and Vittoria was very pleased with the spirituality of the figures.

At that time only Christ, the Virgin, St. John and some angels appeared. Vasari describes it as follows:

... and Michelangelo drew him a Pietà, where we see the Virgin with two little angels and a Christ nailed to the cross, who raises his head and commends his spirit to the Father, who is divine.

Although he speaks of a drawing, the artist ended up making a painting.

This painting is also known from a letter from Vittoria to Michelangelo:

I trusted above all things that God would give you a supernatural grace to make this Christ; after seeing it so admirable that it surpasses, in every respect, every expectation; for, encouraged by your prodigies, I desired what I now see marvelously realized and which is the sum of perfection, to the point that one could not desire more, and not even to desire so much.

In 1547 Vittoria died and such was Michelangelo's affection for her that he recovered the painting and included her as Mary Magdalene embracing the cross of Christ and on her shoulders a scarf symbolizing her widowhood.

Although the original painting has been lost, many drawings and copies made by Michelangelo's disciples have been preserved, among them the one kept in the Co-cathedral of Santa María de la Redonda in Logroño.

Architectural work of Michelangelo

The facade of San Lorenzo

The Medici family had financed the construction of the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence, according to Brunelleschi's design. Begun in 1420, during the visit in 1515 of Pope Leo X the façade was still unfinished with only an enclosure of exposed stonework, and for the occasion, the unfinished façade of the church was covered with an ephemeral construction by Jacopo Sansovino and Andrea del Sarto.

The pontiff then decided to hold a competition for the façade, sponsored by the Medici. Michelangelo won the competition against designs by Raffaello Sanzio, Jacopo Sansovino and Giuliano da Sangallo.

He planned to create a façade representing all the architecture and sculpture of Italy, devising a façade similar to a Counter-Reformationist altarpiece but in reality inspired by the models of profane architecture, enhanced with numerous marble statues, bronze and reliefs.

He made a wooden model made by Baccio d'Agnolo; as it was not to his taste, a second model was made with twenty-four wax figures, on the basis of which the contract for its construction was signed on January 19, 1518.

As Michelangelo wrote, full of enthusiasm: "I have proposed to make of this façade of San Lorenzo a work that will be the mirror of architecture and sculpture for the whole of Italy...".

In the period 1518-1519, Michelangelo checked the marble in Carrara, a useless work, since the pope proposed that the marble should come from the Florentine territory, in the stone quarries of Pietrasanta and Serravezza.

On March 10, 1520, the pope terminated the contract, when the artist complained that the marble intended for the facade was being used in other works. The second wooden model presented and made by his assistant Urbano is preserved in the Casa Buonarroti.

Improvements to the Medici Riccardi Palace

Around 1517, he carried out improvement works on the first floor of the Medici Riccardi palace, where the arches of the loggia (gallery) that had been built on the corner of Via Longa and Via de'Gori were closed, resulting in a more closed and more compact architecture of the building. The windows that Vasari called inginocchiate (kneeling) were also installed. A drawing that must have been used for the model of this palace is preserved in the Casa Buonarroti.84

New Sacristy

Begun at the request of Leo X in 1520, it was under the mandate of Clement VII that a new impulse was given to the construction of the "New Sacristy" in 1523, located in the Basilica of San Lorenzo in Florence, destined to house the sculptural ensemble formed by the tombs of Captains Julian,

Duke of Nemours and Lorenzo, Duke of Urbino, who had died recently, and that of the Magnificent, Lorenzo and his brother Julian de' Medici, and the Medici Madonna, which according to the author Anthony Betram is the first Mannerist work of Michelangelo.

On the opposite side of the transept was the old sacristy built by Brunelleschi and decorated by Donatello. The new construction was to be adapted to the plan of the previous one, which consisted of two squares of different widths connected by an arch and a dome; the walls were plain, framed by pilasters and moldings made of pietra serena, the gray stone of the region.

Michelangelo enlarged the central part, in order to give more space to the sepulchers and altar.

In the vertical design he changed the architecture of the Quattrocento and placed blind windows above the doors; the windows next to the dome were made in the form of a trapezoid to achieve a larger ascent optic. The dome is made with a coffered ceiling of radial coffers.

These coffers are distributed in five rows of decreasing size, which imitate, even in number, those of the Pantheon in Rome; they end in a radial crown, where the lantern begins, of delicate form and perfect beauty; it is the most important contribution to the exterior of the chapel.

Seen from the outside, Michelangelo's renovation of the sacristy of San Lorenzo presents a large dome with a tiled roof, a set of moldings and large windows that favor the play of light and shadow in the interior. Discarded from the first project, where the artist intended the central space for the funerary monuments, these ended up, in the following designs, displaced to the walls, where they were completely integrated into the architecture.

Laurentian Library

Also Clement VII had the idea of building a library in Florence to preserve the entire collection of the Medici family's còdex, and he counted on Buonarroti for this project; the building would end up being known as the Laurentian Library, since it had had a great expansion of its bibliographic collection by Lorenzo the Magnificent at the end of the 15th century A.D.

From 1523 on, once the site was chosen within the convent of the Basilica of San Lorenzo, on the upper floor of the eastern side of the cloister, projects began that would suffer a great deal from a large number of problems. From 1523 onwards, once the site was chosen within the convent of the Basilica of San Lorenzo, on the upper floor of the eastern side of the cloister, the projects began to undergo a large number of variations.

It was necessary to organize different spaces to separate the Latin books from the Greek ones, and they also wanted to distribute the rare books in small rooms, but in the end it was decided to organize everything in a large room.

Efforts were focused on resolving the support of the new structure on the old walls: in the library the ceiling level was lowered and windows were placed very close to each other, thus increasing the luminosity;

the foyer was designed as a circulation area, with a higher height, and windows for lighting were added. In 1533, the pope gave Michelangelo permission to move to Rome, on the condition that he left the completion of the decoration and the access staircase to the foyer.

The coffered ceiling of the library is made with elliptical and rhomboidal motifs; Buonarroti also designed the large reading desks. He made numerous designs for the staircase, and finally, in 1558, he sent the project from Rome, together with a model, to Bartolomeo Ammannati, who was commissioned by Cosimo I de' Medici to build the staircase.

More than thirty sheets of drawings are preserved in the Laurentian Library, although it is known from the correspondence that took place during its elaboration that there must have been many more.

Piazza del Campidoglio

After Florence, he also developed an architectural phase in Rome during the last two decades of his life; in 1546 he was commissioned to develop the Capitoline Square or Campidoglio. During the visit of the Emperor Charles V, Pope Paul III, among the various works for the ornamentation of the city on the occasion of this reception, had some sculptures moved to the Capitoline Hill:

in 1537 he had placed the bronze equestrian statue of Marcus Aurelius, symbol of imperial authority and by extension of the continuity between imperial and papal Rome; this sculpture was to be the starting point of the entire urbanization. Michelangelo, so that there would be a unitary vision, arranged the Palazzo dei Senatori (seat of the town hall) at the back of the square, with staircases tangent to the facade; and delimited on the sides by two palaces:

the Palazzo dei Conservatorio and the so-called Palazzo Nuovo built ex-novo, both converging towards the staircase leading to the Capitol. The buildings, now the Capitoline Museums, were endowed with a giant order with Corinthian pilasters on the façade, cornices and architraves, and projected diverging, not parallel, so that the square was in the shape of a trapezoid, to achieve the optical illusion of more depth.

The motif used in the paving of the square was designed with a curvilinear grid inscribed in an ellipse centered on the base of the statue of Marcus Aurelius, and divided into twelve sections, which recalls the symbol used in antiquity for the twelve signs of the zodiac, alluding to the celestial dome. It is also a reference to Christian architecture, with the symbol of the twelve apostles.

Michelangelo's treatment resembled the type of medieval schemata to coordinate the lunar cycle with other interpretations such as the hours and the zodiac, taking as an example for these symbolic keys those of the 10th century A.D. manuscript of De Rerum Natura of St. Isidore of Seville (which deals with astronomy and geography).

Michelangelo gave the square an extraordinary plasticity, in charge of merging the whole architectural environment. The result is an open space, especially between the two symmetrical palaces, as if it were a hall reached by means of the great central ramp, the Cordonata Capitolina, with diverging balustrades to create a visual effect of unity with the square.

Total unity was not achieved until much later with the construction of the Palazzo Nuovo, designed by Michelangelo to separate the square from the church of Aracoeli. The facades were built, for the most part, after the artist's death, and although they are not a faithful realization of his projects, they do constitute a magnificent composition.

Palazzo Farnese

In the construction of the Palazzo Farnese, Michelangelo replaced Antonio da Sangallo the Younger, who was directing the works at the time of his death in 1546. The building was under construction at the second floor level.

Buonarroti finished the façade before completing the side and rear sections, and had the height of the second floor raised to unify them with the same size as the lower ones. The cornice of the building, which Sangallo had planned to be narrower, was replaced by a larger one with ornamental elements, where the Doric, Ionic and Corinthian orders are mixed.

He also changed the rhythm of the facade with the revision of the central window, which he gave a larger lintel with the extension of the entablature, above which he placed a giant coat of arms more than three meters high.

The rear part of the work was finished years later by Giacomo della Porta.

St. Peter's Basilica

Michelangelo was appointed architect of St. Peter's Basilica in 1546 at the age of seventy-two, upon the death of Antonio da Sangallo the Younger. The construction of the basilica had been begun on top of the earlier Paleochristian one, by order of Pope Julius II and under the direction of the architect Bramante; after the latter's death, Raphael Sanzio took over, modifying the plan and transforming it into a Latin cross.

When Michelangelo was commissioned to carry out the works, he again modified the plan and returned, with slight variations, to Bramante's original idea of a Greek cross, but reduced the four corners of the square so that the smaller areas could have direct light.

He was particularly responsible for the modification of the central dome compared to Bramante's project: he removed the ring of columns and gave it a higher profile. By eliminating the towers, the dome became the predominant element.

He obtained permission from the pope, at the sight of his models, to demolish part of Sangallo's construction and, without substantially altering the interior, he managed to impose his personal style and bring great unity to the whole. Most of the work was carried out between 1549 and 1558.

With slight adjustments to the project conceived by Michelangelo, who left a model for the central dome made between 1558 and 1561, the work was completed 24 years after his death by the architects Giacomo della Porta and Domenico Fontana, with a height of 132 meters and a diameter of 42.5 meters.

Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri

By concession of a bull of July 27, 1561, Pius IV decided to install the Carthusians in the Baths of Diocletian, after their transformation into a church.

Already in 1541 a Sicilian priest, Antonio del Duca, had asked the pope to create a church dedicated to the cult of the angels, and in 1550 he obtained authorization to build fourteen provisional altars, seven dedicated to the angels and seven to the martyrs.

On August 5, 1561, the foundation stone of the church was laid and Michelangelo was in charge of the project, who, according to Vasari, proposed:

... to design it in the form of a cross, to limit the size and to eliminate the lower chapels, whose vaults were to be demolished, so that the upper parts would be those that would form the main part of the church. Its vault would be supported by eight columns, on which the names of martyrs and angels would be engraved; he drew three doors, one to the southwest, another to the northwest and the third to the southeast, as they can be seen today; the main altar, he placed it towards the northeast.

-Ackerman (1997, p. 355)

Work began immediately, but had to stop in 1563 for lack of funds. When in 1565 it became a titular (parish) church with the name of Santa Maria degli Angeli e dei Martiri, a bronze baldachin was commissioned for the high altar, according to a design by Michelangelo, which is now in the museum of Naples. Over the following centuries it has been transformed, making the original design almost imperceptible.

Porta Pia

Pope Pius IV commissioned a project for the Porta Pia, the artist presented him with three projects; the pope chose the one with the lowest cost and construction began in 1561.

The gate was built during the process of urban redevelopment carried out by Pope Pius IV. The new street coming from the Quirinal was named Via Pia in honor of the pope; from then on it continued in a straight line through the Porta Pia, which crosses the city walls; Michelangelo built it in that section to replace another one that was very close to the place called Nomentana.

It was made as a great scenography, at the highest topographic point of the wall, with the façade facing the interior of the city, thus departing from the ancient tradition of facing the gates towards the countryside, as a presentation of the city to the visitor.

The medals minted for the construction of the gate, the work of Giovanni Federico Bonzagni, show how it was originally designed. The project for the external part could not be completed due to the death of Michelangelo in 1565 and the election of a new pope, Pius V, so the work was halted and the external part was solved with a simple wall and a door.

In 1853 Virginio Vespignani restored the attic and, during the period 1861-1868, the exterior door was built.

Michelangelo's Drawings

Michelangelo's drawings form a very numerous and important collection, despite the bonfires he is known to have once made to burn, according to Vasari, "designs, sketches and cartoons made by his hand, in order that no one might see the fatigues he had gone through and the various trials through which his ingenuity had to pass until perfection appeared."

The first drawings attributed to the artist are the copies made in the Florentine basilica of Santa Croce of Masaccio's Tribute and Consecration and the drawing of the Alchemist, of his own invention (now in the British Museum), as well as a copy of Giotto preserved in the Louvre, all from the time of his studies in the palace of Lorenzo the Magnificent, around 1490.

The battle of Cascina

Michelangelo's technique is shown in all its terribilitá in the commission for the decoration of the hall of the Great Council of the Palazzo Vecchio.

In 1503, the new republican government, having chosen Piero Soderini as gonfaloniere, decided to fresco the room, and for this purpose commissioned Leonardo da Vinci to depict The Battle of Anghiari and, on the opposite wall, Michelangelo The Battle of Cascina, thus pitting the two greatest artists of the time against each other.

Michelangelo began the elaboration of the cardboard with the drawing, as it is recorded that in 1504 he had already received two payments. The subject is inspired by the chronicle of Filippo Villani, who, as he narrates, in 1364, the troops of Florence attacked those of Pisa near Cascina and, because of the strong heat, the soldiers undressed to take a bath in the Arno River.

Although the Pisans took advantage of this moment to attack, the victory went to the Florentines. Here Michelangelo demonstrated his great mastery of the nude, along with dynamic movement and creation, to the point of exhausting all expressive possibilities, with a great variety of techniques: some figures are outlined with charcoal; others, with strong strokes, are sfumatoed and illuminated with plaster.

For example, in the Nude with back in the Casa Buonarroti in Florence, the outlines with thick strokes and the shadows in a grid can be appreciated.

As he had to leave for Rome at the request of Pope Julius II, the artist did not go beyond the execution of the cartoons. The fresco executed by Leonardo da Vinci in the hall of the Great Council, The Battle of Anghiari, was destroyed shortly afterwards and is only known from a copy of the central part made by Rubens. Curiously, there is also a copy of the central part of The Battle of Cascina by Bastiano da Sangallo.

In 1515, during a visit to Florence by Pope Leo X, decorations were made throughout the city based on The Battle of Cascina according to Michelangelo's project; it is likely that the cardboard was broken up and given to different artists to be copied to decorate the town for the pope's reception.

Studies on individual figures of this sketch by Michelangelo are preserved in the British Museum and in the Uffizi collection. Vasari describes the complete sketch:

Michelangelo filled it with naked men, bathing in the Arno because of the heat, at the very moment when in the camp the alarm was given of an intended attack. And, as the soldiers rushed out of the water to dress, Michelangelo's inspired hand depicted them, some rushing to arm themselves to help their comrades, others strapping on their breastplates or adjusting their armor, and a large group rushing into battle on their horses.... When they saw this sketch, the other artists were overcome with admiration and astonishment, for it was a revelation of the pinnacle that could be achieved in the art of drawing. Those who have seen these inspired figures declare that they have never been surpassed by any artist, not even by Michelangelo himself, and that no one, never in life, will succeed in achieving this perfection.

-Vasari, 1550; in Hodson (2000, pp. 48-53)

The fortifications of Florence

After the expulsion of the Medici in 1527 and the establishment of the new republic in Florence, on April 6, 1529 Michelangelo was appointed "governor and procurator general of the fortifications" and, in addition to a short stay in Venice, he devoted all his efforts to the improvement of the Florentine fortifications.

All the drawings classified in the Casa Buonarroti are studies for the bastions of the gates and the angles of the medieval walls. The one for the corner of the Porta al Prato d'Ognissanti, in the western part of Florence, is particularly noteworthy for its elaboration.

Michelangelo focused his concern on defensive action and shows his great originality in this kind of drawings which are the only military designs, together with some other by Leonardo da Vinci, in which the trajectories of the cannon shots and their radius of action are established.

The large number of sharp protruding bodies in his drawings provide maximum range, as the bastions were defensive rather than offensive.

The author's ideas were destined not to be accepted, and in some of his late drawings one can already see the elimination of blind spots, which could not be protected, surely because of some criticism received from military experts; these later designs, the closest to those used later in the Baroque period, are very similar to those proposed by the military engineer Vauban in his work Manière de Fortier (1689).

Michelangelo's Other drawings

For the vault of the Sistine Chapel the artist made a series of drawings in the form of sketches, where the traces of Mannerism already evident in Michelangelo can be seen:

within this group are the studies of the nudes preserved in the British Museum in London, the studies for the Sibyl Lybica, with different versions, from the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, various studies of figures, a sanguine of Christ in limbo and a few drawings on the theme of the Resurrection.

At the beginning of the 15th century A.D., a type of perfectly finished drawing appeared in Italy, to be given as a gift: Leonardo da Vinci, in 1500, made a series to offer to a patron. Michelangelo also made some series, which he gave as gifts to young people for whom he felt some special affection, but the great majority were to be given to his young esteemed Tommaso Cavalieri, which Vasari justified as exercises in apprenticeship:

... so that he would learn to draw he made him many plates, drawn with black and red pencil, of divine heads; and then a drawing of a Ganymede snatched to heaven by the bird of Jupiter, a Titius whose liver is devoured by the eagle, the Fall of the chariot of the Sun with Phaethon and a Bacchanal of children, all very singular works, drawings never seen before of such excellence.

In the drawing of The Pietà that he gave to Vittoria Colonna around 1540, Michelangelo's transformation is evident in the style.

In this work, the figure of Christ is treated with great delicacy, he sought organic symmetry with his mother Mary looking towards heaven; she extends her arms half-crossed upwards, while her Son lets them fall downwards, all in a symmetrical composition reinforced by the two side figures of some children and the cross in the background, which divides the cardboard into two equal halves and bears an inscription taken from Dante's Cantos de El Paraíso:

"Non vi si pensa quanto sangue costa" (One does not think how much blood it costs).

Numerous drawings are preserved, especially in sanguine:

- Study: Saint Anne, ca. 1505, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

- Ideal Head, red chalk drawing, ca. 1533, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

- Two naked men fighting, ca. 1545-50, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

- Crucifixion, ca. 1550-55, Louvre Museum, Paris.

- Epiphany, ca.1550-53, British Museum, London.

- Descent from the Cross, red chalk drawing, ca. 1555, Ashmolean Museum, Oxford.

- Study of a nude man, done in pen, Musée du Louvre, Paris.

- Study of a man's right shoulder, chest and upper arm and Study of a man's right arm. Both belong to the Museo del Prado, where they entered in 1931 thanks to the Fernández Durán bequest. Preparatory works for the Sistine Chapel, they were identified as works by Michelangelo in 2004.

Poetic work of Michelangelo

As a poet, Michelangelo has left about three hundred compositions that occupy an outstanding place in the lyric poetry of the 16th century A.D., where his energetic and austere tone and a continuous tension towards an ardent expressive immediacy stand out.

The metrical forms that abound most are sonnets and madrigals, although he also wrote some tercets. According to Ascanio Condivi, around 1503, Buonarroti devoted himself to reading " he spent some time doing nothing in the art of sculpture, to give himself to reading the poets and orators in the vulgar language, and to making sonnets for his delight. "

His training carried out in the palace of Lorenzo the Magnificent and based on the Neoplatonic thought of the humanists Pico della Mirandola and Ficino, makes it easier to understand Michelangelo's poetry, because of the great dissatisfaction he always had with himself and with all his environment,

for the idea of "the presence of spirituality in the material", for his enthusiasm for aesthetics and beauty; with poetry, which can be considered quite influenced by Petrarchism, the artist managed to express all his amorous affections and his religious doubts.

The first sonnets were on subjects related to his artistic works, such as the one dedicated to the statue of the Night in the Medici tombs, which read: "It is pleasant for me to sleep, and more to be made of stone - while evil and shame last. Not to see, not to feel, is my fortune; do not wake me, no; speak softly. "

Instead, he employs a humorous and burlesque tone in sonnets written when he was working on the painting of the vault of the Sistine Chapel, around 1510, and addressed to his friend Giovanni da Pistoia, where a drawing of the author having paint falling on his face appears in the manuscript; in the sonnet, he had compared his face on a "rich pavement" and described himself as a "corpse of paint." Begging his friend to redeem him:

"Defend you now, Giovanni, my dead painting and my honor, for it is not in a good place, nor am I a painter".

Later and more numerous are those made for Tommaso Cavalieri, inspired by Petrarch, the first is dated 1532, where he deals openly with love and one can appreciate to what extent Michelangelo was consumed by passion for Tommaso:

"may this time, these hours, and the sun, the light, stop on his face, and may I feel your complete gift, my Lord, desired since then in my unworthy body that embraces you". The inordinate praise for the young man is also seen in the letters he addresses to him, dated January 1, 1533, Michelangelo declares:

Your lordship, the only light of the world in our age, will never be satisfied with another man's work because there is no other man who resembles you, none who equals you..... It grieves me greatly that I cannot recover my past, and thus longer be at your service. As it is, I can only offer you my future, which is short since I am old..... That is all I have to say. Read my heart as the pen is unable to express itself well.

Or in this other: "Your name nourishes my heart and soul, and fills both with such great sweetness that I feel neither sadness nor fear of death since I have had you in my memory".

The poems he dedicated to Vittoria Colonna were mostly religious in theme, as they both had concerns about the same thing, and focused on sin and eternal salvation, already in a tone of anguish and bitterness. In one madrigal he describes the friend as "a true messenger between heaven and himself, a divine woman to whom he implores benevolence and condescension in order to raise his misery to the height of the tortuous path of beatitude. "

The most interesting aspect of the poems of this period is Michelangelo's synthesis of Neoplatonic theories and the practice of Christianity turned towards the spirit. After Vittoria's death, Buonarroti finds himself in a state, according to Condivi, "that for a long time seemed mad",

he enters a kind of drift and is dragged down by his religious obsessions; all this makes him compose a series of pessimistic poems where in a radical way he exposes his absolute disappointment of the value of art.