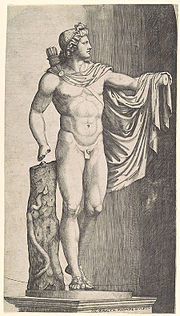

The Apollo Belvedere or Apollo of the Belvedere is a marble statue representing the Greek god Apollo, which is part of the collection of the Pio-Clementino Museum, one of the Vatican Museums. Its dating and authorship are disputed and its provenance is unknown, but it is generally considered to be a Roman copy of a Greek original that was lost.

Rediscovered in the Renaissance, the Apollo was displayed in the Vatican's Cortile del Belvedere beginning in 1511, and from there it received its name. It soon became famous, and for a long time was considered the ideal representation of male physical perfection and one of the most important relics of classical antiquity.

It was copied many times, reproduced in widely circulated engravings, and assumed the role of one of the main symbols of Western civilization. From the mid-19th century on its prestige began to decline, and in the first half of the 20th century it reached its lowest level, seen as an unimpressive creation.

Today it has regained some of its former fame, and although many scholars are still reticent about its artistic merit, it has established itself as the best known representation of the god, and as a very popular icon.

The god Apollo Belvedere

Apollo was one of the most important and popular gods in Greek mythology. One of the twelve Olympians, he was the son of Zeus and Leto, and the twin brother of Artemis. His attributes and functions were countless, which made him one of the most revered gods of Ancient Greece, preserving his prestige also in the Roman era.

His myth has remote origins, and in Homer's time he was already prominent in the Greek pantheon. He was identified with the sun and the light of truth, reason, and conscience. God of prophecy and artistic inspiration, he was patron of the most famous oracle of antiquity, the Oracle of Delphi, and leader of the Muses.

He was also a civilizing and pacifying god, presiding over the laws of religion and the constitutions of cities. Initiator, pedagogue, and the perfect erastes, he was the symbol of eternal youth and the protector of young people entering adulthood.

He was the god of sudden death, of plagues and diseases, but also the god of healing and protection against evil forces. In addition he was the god of beauty, perfection, harmony and balance, he was connected to nature, herbs and flocks, and was the protector of shepherds, sailors and archers.

He had numerous loves and great offspring, and was associated syncretistically with numerous gods of other traditions. His symbolism and iconography have crossed the centuries and remain influential in Western culture to this day.

Description and origin's Apollo Belvedere

Slightly oversized (2.24 m), the Apollo Belvedere stands in a dynamic attitude, as if walking. It rests on its right leg, which comes forward and leans against a tree trunk where a snake climbs, while the left, slightly bent, is behind. He is wearing sandals, and his athletic but softly shaped body is naked; he is still young, but already a grown man, as his impassive countenance shows;

however, he remains impudent as an image of eternal beauty and youth, his attributes; a cloak wraps itself around his lap, falls down his back, and its folds continue to wrap around his left arm, stretched horizontally.

The right arm is lowered, resting on top of the torso, and the head turns to her left, adorned by a complex hairstyle of her long, ringed hair. From his right shoulder descends to his chest a strap that wraps around his torso and holds, from the back, a chest of arrows.

Despite his fairly good state of preservation when he was rediscovered, his hands were missing, essential elements for identifying the attributes he carried and the action in which he would be engaged. It is generally believed that he would be in the act of shooting an arrow, whose bow would be in his left hand.

Others have imagined that this hand would hold the aegis of Zeus, or that the right hand would hold a laurel branch, or an arrow. There are some traces on the trunk of the tree that have been interpreted as fragments of a laurel branch ornamented with banners.

Nothing is known about its provenance, its authorship is uncertain and the stylistic analysis is inconclusive. It is generally believed to be a Roman copy from the Antonine era of a lost Greek bronze original, with authorship attributed sometimes to the Athenian Leocares, active in the late classical period, and sometimes to an unknown sculptor from the Hellenistic period, but it may also be an original Roman creation in an eclectic retelling of the classical Greek canon.

The Apollo Belvedere has been identified historically with a statue of Apollo attributed to Leocares cited by Pliny the Elder and Pausanias as being installed in front of the temple of Apollo Patroos in Athens, and this reference was often repeated as evidence of authorship. If the link is correct, this would place its dating between 350 and 325 BCE.

The problem is that both Pliny and Pausanias cite the work but do not describe it, making the citation weak evidence, and no other work reliably attributable to Leocares has survived, which could establish definitive recognition by stylistic affinities.

On the other hand, it bears a great stylistic resemblance to the Diana of Versailles, a sculpture by tradition attributed to Leocares, and it has already been suggested that both statues might originally have formed the same ensemble.

Recently fragments of what appear to be molds of Apollo were found in an ancient sculpture workshop in Baiae, southern Italy, along with other molds that have been dated to the classical period.

His dating is made more problematic by the fact that several of his features are found not to belong to typical classicism, but may be variations introduced by the copyist. Brunilde Ridgway has pointed out that the style of his hairstyle was not documented in classical times, only appearing in Hellenism and again among the Romans.

The style of his sandal has also been put up for debate. Apparently it is a model that cannot be dated earlier than the 3rd century (Ridgway) or 2nd century BC. (Albertson), being possibly a Roman invention.

If this sandal is not poetic license by the copyist, it would make the original Apollo a definitely Hellenistic or Roman creation, but this, in the absence of other copies, cannot be proven. Likewise, his posture, with the left arm raised, the body in slight torsion, and the movement of the legs are common Hellenistic traits.

Apollo Belvedere's Rediscovery and restoration

Even the circumstances of its rediscovery are not entirely clear, and there are several assumptions about it. Apollo only became notorious in connection with cardinal Giuliano della Rovere, who had possessed it since the late 15th century.

It may have been unearthed in the area of the Church of St. Peter in Chains in Rome, in Nero's villa in Anzio, or in Grottaferrata, where Giuliano was abbot in commendam.

While he was cardinal, Giuliano kept it in the gardens of the Basilica of the Holy Apostles in Rome, but, becoming pope (as Julius II), he transferred the work in 1511 to the Vatican palaces, being installed in the Cortile del Belvedere, from which it received its nickname (today it is displayed in the Cortile Ottagono of the Pio-Clementino Museum).

In 1532 a restoration was ordered. Giovanni Montorsoli removed what was left of the right hand, completed losses on both arms, slightly altered the position of the right forearm, added the missing top of the arrow arch and increased the height of the tree trunk, removed a marble bridge between the right thigh and the trunk, and recreated the two hands, as well as repairing various minor superficial damage throughout the statue.

The penis, also missing, was not restored. Later Montorsoli's restoration was challenged. The main criticism of his work was the disproportionate hands he created, which seemed too elongated. Another addition was made by order of Pius IV, concealing the genitalia with a fig leaf. More recent restorations by Guido Galli (1924) removed part of the old reinstatements.

Apollo Belvedere's Fame

Apollo's fame in antiquity is unknown. Winckelmann indirectly indicated that it must have been considered important, taking as plausible the hypothesis that it had been found in the ancient villa of Nero, who had spent a fortune to decorate it.

In recent times, Albertson also suggested that it must have been a celebrated work, but was surprised at the absence of more copies, as would be expected in such cases. In any case, since it was again displayed in public it was hailed as a masterpiece, and immediately clothed with political significance.

In a poem, the humanist Evangelista di Capodiferro used it to lend an Apollonian dignity and luster to Julius' pontificate. The pope himself made frequent allusions to the sun-god of Greek mythology and to the statue in particular, establishing an intimate symbolic association with it.

Remember that during this period, the Renaissance, the classical tradition had been greatly reinvigorated, becoming an important part of the language of scholarship and serving the powerful as an instrument of self-glorification.

Apollo, as god of light, consciousness, civilization, beauty, arts and reason, but also of prophecy, became a tutelary image for artists and art theorists, who were engaged in developing a figurative art based on rationalism, scientific anatomical study and geometry, together with a conception of art as a divine inspiration.

The chance finding of his statue at this time significantly expanded the popularity of the god, and the relic gained continental fame with the wide circulation of Raimondi's engraving.

Other reproductions multiplied, his image was transposed into other contexts, illustrated anatomy books, and influenced other visual artists, including Dürer, Michelangelo and Goltzius, and literati such as Giambattista Marino. By 1540 wealthy collectors and members of European royalty were already making requests to acquire copies.

Its prestige continued to grow during the 17th century, given the influence it had on Bernini, the most celebrated sculptor of the Baroque, and was reinvigorated in the 18th century among neoclassical artists, antiquarians, and Enlightenment philosophers.

Its visitation was obligatory for those on the European Grand Tour, and it was often presented as the crowning achievement of an artistic-spiritual itinerary, an epiphany beyond which nothing else would need to be seen. For Winckelmann, the great theorist of the neoclassical movement, it embodied, of all the works of antiquity, the highest ideal in art:

"The artist built his work entirely on the ideal, and used in its structure only the material strictly necessary to convey his idea and make it visible. In the presence of this miracle of art I forget everything else, and rise to the heights for the purpose of contemplating it in the dignified manner it deserves. My breast seems to expand and gasp in reverence, like the breasts of those infused with the spirit of prophecy."

Other luminaries of Neoclassicism echoed Winckelmann's praise. Goethe, on his trip to Rome, said that he had, "with that sublime air of youthful freedom and vigor," along with a few other exceptional works, won his heart "to such an extent that everything else was obscured," and Schiller saw him as the ideal embodiment of complete humanity, uniting grace and dignity in one person.

Houdon was inspired by him for his own Apollo in bronze, Hogarth said he looked superhuman, and painters like Allan Ramsay and Joshua Reynolds used his posture and movement as a model to dignify portraits of members of the elite.

Copies of him were made for the major art collections and museums and major colleges of Europe, and he became known to American artists through prints, copies, and the transatlantic dissemination of the writings of Winckelmann and other theorists.

The masterpiece also aroused the greed of Napoleon Bonaparte, who confiscated it from the Vatican in 1797 and brought it to France. It was received in Paris the following year with a triumphal parade and much government propaganda, being installed in the Central Museum of Arts (the future Louvre Museum) in 1800 as the conqueror's greatest trophy.

Meanwhile, Antonio Canova, the great exponent of neoclassical sculpture, had created, inspired by the ancient work, his Perseus with the head of Medusa, purchased by Pope Pius VII to replace the stolen relic and nicknamed "The Comforter", since the loss had been much lamented by the Italians.

In 1815 the work was returned to the Vatican by the same Canova, who negotiated with the French on behalf of the pope for the repatriation of several treasures.The Jason with the Golden Velocus, a sculpture that established the international reputation of Canova's greatest rival, Bertel Thorvaldsen, was a response to both the Apollo Belvedere and the Canovian Perseus.

However, among the Romantics his fame began to waver. While Lord Byron still sang him beautifully in Childe Harold, Melville considered him "the glory of the Vatican," and Beethoven kept a copy in bust form in his cabinet, while Emil Braun described him in an 1855 tour guide written "for travelers, artists, and

lovers of antiquity" as "sublime" and capable of taking people "to the highest regions of poetry by the contemplation of such beauty," Hazlitt dismissed him as "positively bad," Ruskin was disappointed by what he considered an excessively deadly appearance for a god, and Dostoyevsky called him a "useless idol."

Walter Pater was the first to identify some of the enthusiasm triggered by the statue with its homoerotic appeal, an association he traced back to Winckelmann himself, but which was also linked to the original myth of the god, among whose attributes was that of being the perfect erastes.

Incidentally, during the Victorian period his nudity was interpreted in a double discourse: on the one hand it came to be considered a delicate and even anti-educational, if not scandalous, subject, a concern that extended over all classical statuary; caricatures even appeared showing him dressed in modern attire.

On the other hand, for the less moralistic elite, the nudity of Apollo and other ancient works was an acceptable and elegant way, referenced and sublimated by its classical aura, of presenting male nudity publicly to a sophisticated and well-educated society of men and women who could comfortably handle the erotic feelings aroused by the image,

integrating itself into an important current of thought that attempted to articulate the concept of Greek love in its various manifestations with art, academic culture, and the society and sexuality of modern Europe, a discussion that resonates to this day.

In any case, for the purposes of academic education in anatomy and proportions, the statue continued to be considered a good model for art students throughout the 19th century, even though its fame on this specific topic had been supplanted by that of the Elgin Marbles.

Among practitioners of wrestling and the nascent bodybuilding, it was also held up as a model, along with other masterpieces of antiquity such as the Apoxyomenos and the Farnese Hercules.

Despite fluctuations in his aesthetic appreciation, it is difficult to overestimate his influence on Western culture over centuries. During the height of European colonialism the Apollo Belvedere came to embody the very identity of Europe.

The hegemonic, patriarchalist, xenophobic theories that then influenced Euro-American scientific discourse, and which were not new, naturally invoked him as the "concrete proof" of the alleged "superior" beauty of the white man and the supremacy of Western civilization over other peoples and geographies.

This line of interpretation became particularly useful to German Nazis and other eugenics advocates active in America, who appropriated classical iconography and symbolism to justify their totalitarian goals.

As an ironic counterpoint to this reading of Apollo as the paradigmatic white man, at the same time theories emerged, based on some anatomical evidence and ancient literary sources, that the statue, as well as the entire Greek canon of proportions, had been derived from the Egyptian canon, which used the Negroid body as a model. Recently this hypothesis has been recovered, but it is surrounded by controversy.

In addition to the negative repercussions of politicized approaches, this sculpture, like the classics in general, had to face on the aesthetic terrain the additional attack of the modernists, interested in overthrowing the academic tradition in which it figured prominently.

The discredit of the classical legacy at this time was attested to by Kenneth Clark in a 1969 commentary: "Throughout the four hundred years after it was discovered Apollo was the most admired piece of sculpture in the whole world. It was Napoleon's great prey. Today it is completely forgotten save by the tour guides, who have become the only relays of traditional culture."

Lately Apollo Belvedere has managed to regain some luster for his image, although many critics still see him as a cold and conventional creation. He hardly fails to be mentioned in recent books on art history, his effigy was included in the emblem of the Apollo 17 mission as a symbol of continued space exploration, and in a more informal way, he has become a popular icon.

Reproductions of him for tourist consumption are currently found by the thousands in Rome, throughout Italy and other countries, in statuettes, medals, postcards and mass reproduced prints, in iconographic terms he has become the best known among all representations of the god Apollo,

and after his pose served as a model for many portraits of eminent personalities in the 18th century, his figure has been resurrected in contemporary "body culture" as a standard of male beauty.