The Discobolus (literally, "the discus thrower", Greek, Δισκοβόλος, Diskobόlos) is one of the most famous statues of antiquity. Generally attributed to Myron, an Athenian sculptor of the fifth century BC. (-450 BC), it represents an athlete throwing the discus.

Myron, a representative of early classicism, was famous for his representations of athletes, which explains the attribution. Moreover, this work is mentioned by Pliny the Elder in his Natural History, where the author lists the works made by Myron.

Description of Discobolus

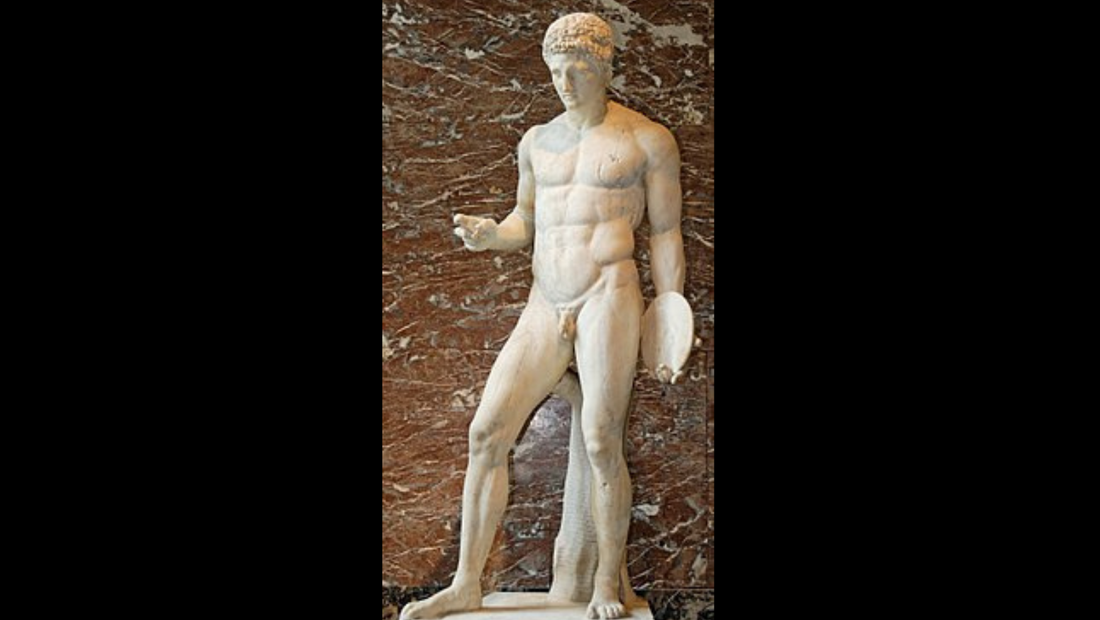

The original statue represents a naked athlete - like all Greek athletes -, hairless, frozen as he prepares to throw his discus. The head is turned to the side. Lucian of Samosate describes him thus: Did you not see," he said, "in the courtyard, as you entered, this beautiful statue, the work of the sculptor Demetrius? Is it not this man holding a discus, and that we see bent over in the attitude of throwing it?

His face is turned towards the hand that holds the discus, and gently bending his knee, he seems ready to get up as soon as he has thrown it. - This is not the one; the discobolus you mean is a work by Myron. " The movement unfolds to the side, giving a two-dimensional composition (which is characteristic of pre-classicism).

The torso faces the viewer, while the legs and buttocks are in profile. Only the right leg carries the weight of the whole. The effect produced by this formal choice is that the whole is almost flat, as if it were more of a high relief than a roundel. The composition is geometric, theoretical. Indeed, the edge of the pectoral muscles is clear, the musculature is made of plastic and theoretical forms which answer each other.

The character, while in full effort, is impassive, the look serene and without expression. To the modern viewer, it may seem that Myron's desire for perfection caused him to suppress too radically the expression of tension in each of his muscles. The eyelids are heavy, the nose straight, the mouth fleshy and slightly ajar, the jaw thick, the chin strong.

His face is idealized so that his image gains a timeless aspect. The artist has chosen to depict the brief moment when the discobolus reaches the point of release, after the start of the movement and immediately before the throw: this moment is so brief that contemporary athletes still wonder if it really exists.

Its pose seems implausible to us for an effective throw, but ancient athletes rotated only three quarters of a turn, compared to today's one and a half turns. This type of rotation may have been designed to increase the difficulty of athletic performance.

It is this pose that gives the statue its remarkable vivacity. It is for this reason that it is cited by Quintilian in his Institution of Oratory when he pleads for the introduction of movement and variety into rhetorical discourse.

Discovery of Discobolus

One hypothesis is that the Discobolus belonged in fact to a group. Myron has, in fact, composed several statuary groups, such as Heracles, Zeus and Athena or Athena and Marsyas, which has come down to us today. The Discobolus could belong to a group representing Apollo and his lover Hyacinth. According to the legend, Apollo kills his lover during a discus throw.

One version of the myth explains that the discus was diverted from its course by Zephyr whose advances Hyacinth had rejected. Pliny mentions an Apollo sculpted by Myron in his Natural History. The Discobolus could represent Hyacinth alone. Hyacinth was the object of a cult among the Spartans, who paid homage to him in the sanctuary of Amyclaeus.

He could have played a role in a rite of passage cycle for young soldiers. The original statue could also be a votive work offered by an athlete after his victory in a discipline. It is not known on which site the original bronze statue, now lost, was located. Only copies in marble from the imperial period remain. The most famous of these is the Lancellotti Discobolus, considered the most faithful reproduction of the original.

The work was discovered on Mount Esquiline in the eighteenth century and sold to the Massimo family, which later became Massimo Lancelotti. Made in the first century under the Antonines, it is currently in the collections of the Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, a branch of the Roman National Museum, in Rome.

Another known copy, exhibited in the same museum, is the Discobole Castelporziano, discovered mutilated (the head is lost) in the eponymous village in 1906, among the ruins of an imperial villa. This copy is more realistic in its treatment of the volumes and testifies to the technical evolutions that have occurred since then between Greek classicism and imperial Roman sculpture.

Until the discovery of the complete statue of Discobolus Lancellotti in 1781, several busts of Discobolus had been wrongly attributed to compositions other than Discobolus.

This is the case of the "Gladiator" in the Capitoline Museums in Rome or the "Diomedes" found in Ostia in 1772 and now in Bowood House (Wiltshire). One of the most famous copies today is the one on display in the British Museum, the Townley Discobolus.

Townley purchased a Roman copy of the Discobolus in 1794, excavated from the Villa Adriani in Tivoli. The Townley Discobolus6 does not look back, because its head comes from another statue, even if Townley's intermediary in Rome assures him that it is the same marble and that the said head was found next to the body of the Discobolus.

While today such restorations would not be practiced, the criteria were different in the eighteenth century. Collectors expected complete sculptures, even if this meant significant alterations. Moreover, it was thought that the Romans, when they themselves had copied Greek originals, had worked to "improve" them.

The restorers of the 18th century saw themselves as the heirs of this tradition. In fact, the practice of imitation was far from being seen in a negative light by the Romans and thus, numerous copies of quality works circulated and copies of the Discobolus flourished throughout the Empire. Among them, the Discobolus (known as the Carcassonne Discobolus) now on display in Toulouse.

Discobolus's Representation in Greek culture

The word discobole comes from the ancient Greek δισκοβόλος / diskobolos, "discus thrower". The Greek discus was a stone or bronze puck about 20 cm in diameter. It weighed more than 5 kg. Before the discovery of the Lancellotti Discobolos, only static discobolae were known, at rest, simply holding the disc in their hands, which today are called discophores, even Pliny the Elder refers to them as "discobolae ".

The statue of the Discobolus appears on the commemorative coin of 2 euros struck by Greece on the occasion of the Olympic Games of Athens of 2004.

'Discobolus's Posterity

The Discobolus in modern history

In 1936, as part of the celebrations associated with the organization of the Olympic Games, an exhibition, Sports of the Greeks, showed several representations of the Discobolus in Berlin, including the small bronze statuette in the Munich Glyptothek. The Greek statuary and the perfect bodies which it represents fascinate the Nazi ideologists.

Hitler was even so fascinated by the Discobolus that he purchased it in 1938. Indeed, he had the Discobolus purchased from the Lancellotti family for the equivalent of $327,000 at the time.

This representation of an exemplary body, with perfect musculature, participates for Hitler in the demonstration of the Aryan superiority; indeed, he posits in Mein Kampf that the Germanic Aryan peoples, by migrating southward, settled in pre-classical Greece and constituted the driving forces of the Dorian invasion (coming from the North of Greece).

Hitler drew the aberrant conclusion that the Greeks were reincarnated in the Germans and that Greek classical art in fact expressed the greatness of the German people.

After the war, the Americans pressured the statue to return to Rome. The German scholars argued that it had been legally purchased, but the American military government and the Italian intelligentsia worked together to have it returned to Italy, not to the Lancellotti family, but to the national museum. This was done in November 1948.

The same year, the Olympic Games were organized in London. An order was placed with the designer Walter Herz to start designing the campaign for the buses. The poster shows the Townley Discobolus suspended above the Olympic rings, with the Palace of Westminster in the background.

This poster is a clear response to the Nazi's propagandistic use of the Discobol. The Houses of Parliament represent the oldest democracy in the modern world, the Discobolus refers to the world's first democracy and the idea of intellectual freedom associated with ancient Greece.

Artistic evocations

In 1932, Leni Riefenstahl opened her film about the Berlin Olympics, Olympia, with a directed tribute to the Discobolus: the camera moves slowly through the ruins of Olympia and the Acropolis before lingering on several iconic statues of Greek art and finally stopping on the Discobolus from which Erwin Huber, a German athlete, emerges. The message is sadly clear: the glories of ancient Greece are reborn in Nazi Germany.

The Discobolus being one of the most famous sculptures of Antiquity, Uderzo transposes it in Les Lauriers de César, where a slave reproduces the pose of the statue.

In 1998, the artist Sui Jianguo proposed a resin discobolus, dressed in Mao's costume, intended to be a symbol of the constraints suffered by Chinese artists and intellectuals during the communist era. He repeated the sculpture in 2008 with different and diverse materials: glass, ceramics.

The same year he attacked Chinese productivism and mass production by ironically dressing several interchangeable and anonymous discoboles in a costume similar to that of Chinese executives.

In 2008, on the occasion of the Beijing Olympics, the Discobolus was exhibited in China, as part of an exhibition on the ancient Olympics. It was so successful that it became the centerpiece of another exhibition, The Human Body in Greek Art and Society. Chinese artists then became passionate about this figure.

During 2013, the Croatian artist Ivan Ostarcevic gives the features of Captain America to a discobolus.

In 2017, the French artist Léo Caillard gave the sculpture a new lease on life. He sculpts the Lancellotti Discobolus again in chrome galvanized resin and adds several dozen white neon and led horizontal light circles, all horizontal. This work will be exhibited in 2019 at the Musée Saint-Raymond, Musée des Antiques de Toulouse as part of the temporary exhibition Age of Classics! Antiquity in Pop Culture.