The Farnese Hercules (Italian: Ercole Farnese) is a 317 cm high Hellenistic High Period marble sculpture of Hercules by Glycon (or Glykon) of Athens, dating from the early second century, housed in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples.

It is probably an enlarged copy made and signed by Glycon, who is otherwise unknown; the name is Greek but he may have worked in Rome. Like many other ancient Roman sculptures, it is a copy or version of a much older Greek original that was well known,

in this case a bronze by Lysippus (or someone close to him) that would have been made in the fourth century B.C. On the rock, under the club, is the signature of the copyist Glykon, a first-century Athenian sculptor.

This original survived for over 1,500 years until it was melted down by the Crusaders during the Siege of Constantinople (1204). The enlarged copy was made for the Baths of Caracalla in Rome (dedicated in 216 AD), where the statue was discovered in 1546.

It entered the Farnese collection and is now in the National Archaeological Museum in Naples. Hercules on a heroic scale is one of the most famous sculptures of classical antiquity and determined the image of the mythical hero in the European imagination.

A massive marble statue, it depicts a muscular, but tired Hercules, leaning on his club, over which is draped in part the skin of the Nemean lion. In the myths about Heracles, killing the lion was the first of his Twelve Labors, suggested by the apples of the Hesperides that he holds on his back.

The genre was well known in antiquity, and among many other versions, a Hellenistic or Roman bronze reduction found in Foligno is in the Louvre. A small copy in Roman marble can be seen in the Museum of the Ancient Agora in Athens.

History of Farnese Hercules

The rediscovered statue soon became part of the collection of Cardinal Alexander Farnese, grandson of Pope Paul III. Alexander Farnese was well placed to build up one of the greatest collections of classical sculpture assembled since antiquity.

It was kept for generations in its own room in the Farnese Palace in Rome, where it was surrounded by frescoes depicting the mythical exploits of the hero, made by Annibale Carracci and his workshop, executed in the 1590's. The Farnese statue was moved to Naples in 1787 along with the bulk of the Farnese collection and is now on display at the National Archaeological Museum.

The sculpture has been reassembled and restored by level. Guglielmo Della Porta, a student of Michelangelo, restored the sculpture by inserting the missing parts. According to a letter from Michelangelo, the head was recovered separately from a well in Trastevere and purchased for Farnese through him.

The legs made to complete the figure were so prized that when their original was recovered from the excavations underway in the Baths of Caracalla, Della Porta's were retained on Michelangelo's advice, in part to demonstrate that modern sculptors could stand direct comparison with the ancients.

The original legs, from the Borghese collection, were only reunited with the sculpture in 1787, at the time of the Bourbons of Naples, when it was decided to restore the antique parts. Today, in the archaeological museum of Naples, it is possible to see on the wall behind the Hercules the two calves sculpted by Guglielmo Della Porta.

Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, in his Journey to Italy, recounts his various impressions upon seeing the Hercules with each pair of legs, marveling, however, at the clear superiority of the originals.

Numerous engravings have made the Farnese Hercules famous. In 1562, the discovery was already included in the set of engravings of the Speculum Romanae Magnificentiae ("Mirror of the Magnificence of Rome") and connoisseurs, artists and tourists marveled at the original, which stood in the courtyard of the Farnese Palace, protected under the archway.

In 1590-1591, during his trip to Rome, Hendrik Goltzius sketched the statue in the courtyard of the palace. Later (1591) he reproduced the less common rear view in an engraving that emphasized the already exaggerated muscular form, with bulging and tapering lines that spill over the contours.

The young Peter Paul Rubens made quick sketches of the planes and mass of the Hercules statue. Before photography, engravings were the only way to get the image into many hands.

In 1787, thanks to the inheritance obtained by Charles III (King of Spain), son of Elisabeth Farnese, the entire Farnese collection was transferred to Naples and placed first in the palace of Capodimonte, built precisely for this purpose, and later in the National Archaeological Museum of Naples.

The sculpture was admired from the beginning, with reservations about its exaggerated musculature appearing only at the end of the eighteenth century. The Hercules' fame was truly European, and anecdotes about it during the French Revolution and Napoleonic spoliations are numerous.

In France, the failure of the abduction of the Farnese Hercules seems to have been a real concern of the revolutionaries at first, and then of the Napoleonians. Mgr Henri Grégoire, declared before the National Convention of 1794: "If our victorious armies penetrated into Italy, the abduction of the Apollo of Belvedere and of the Hercules Farnese would be the most brilliant of conquests.

It is Greece which adorned Rome: but the masterpieces of the Greek republics adorn the country of the slaves (that is to say Italy?).

The French Republic should be their permanent home." Another famous anecdote is told by Antonio Canova in his writings: on October 12, 1810, the sculptor was presented to Napoleon by General Duroc in order to express his desire to return to Italy, but Napoleon objected, pointing out that the omission of the Hercules from the museum he had established in Paris was the most important gap in the collection.

To which Canova replied, "At least leave something to Italy. These ancient monuments form a chain and a collection with infinite others that cannot be transported from either Rome or Naples. The sculpture was crated and ready to be shipped to Paris before the Napoleonic regime fled Naples. The other works, which were subject to Napoleonic spoliations throughout Italy, met a different fate.

Description of Farnese Hercules

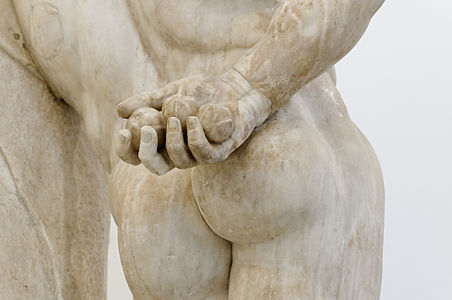

Hercules is caught in a rare moment of rest. Leaning on his gnarled club which is draped with the skin of the Nemean lion; he holds the apples of the Hesperides, but hides them behind his back, in his right hand.

Hercules personified the triumph of man's courage over the series of trials set by the jealous gods. He, the son of Zeus, was allowed to achieve immortality. By the classical era, his role as savior of mankind had become more pronounced, but he also possessed mortal flaws such as lust and greed.

Lysippus' interpretation reflects these aspects of his mortal nature. This statue represents Hercules, tired at the end of his labors, resting on his club, holding in his right hand, behind his back, the golden apples stolen from the Hesperides.

Farnese Hercules Copies

Numerous copies in marble and bronze were made, some in ancient times, and many from the eighteenth century onwards.

Ancient copies

The statue, in full view, was very popular with the ancient Romans, and copies have been found in palaces and gymnasiums. Another, cruder copy stood in the courtyard of the Farnese Palace; one with the mock (but probably ancient) inscription, "Lykippos," has stood in the courtyard of the Pitti Palace, Florence, since the sixteenth century. Early copies of the statue include:

- Hercules, 1st century, Roman copy, Uffizi Museum, Florence.

- A Hercules similar to the one in Naples is present in the hall of honor of the palace in Caserta, found with the Farnese Hercules and named Ercole Latino.

- The Weary Herakles, a heavily broken Roman marble statue, was discovered during excavations in 1980 in Pergé, Turkey. The looted upper torso was sold to the Museum of Fine Arts (Boston) in 1981; it was returned to Turkey in 2011 and is now on display with the rest of the piece at the Antalya Museum.

- The Ercole Curino, also in bronze on a reduced scale from the second century B.C., was found in Sulmona and is now kept in the National Archaeological Museum of Abruzzo in Chieti.

- Colossal statue of Hercules, discovered in the baths of Hippo Regius (Annaba), Algeria.

- Heracles at rest, Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg.

- Headless marble statue from the late Hellenistic period, severely damaged, recovered from the wreck of Antikythera in 1901, National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

- Headless statue in the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnography of Izmit.

- Headless torso, broken, found in the public baths of the Roman and Byzantine village of the Jezreel valley.

- Headless torso, broken, from the Amphiareion of Oropos, National Archaeological Museum of Athens.

- Headless torso, broken, from the first or second century, in the Musée Saint-Raymond in Toulouse.

- Statuette of the first century, in the Detroit Institute of Arts.

- Bronze statuette with silver inlaid eyes, 40-70 A.D., Getty Villa.

- Ancient bronze copy (reduced 42.5 cm) discovered in Foligno (province of Perugia) and exhibited in the Louvre.

The type of Hercules Farnese is also used in Roman funerary statuary, as can be seen on the smiling boy in the Louvre. In this statue, the child is playing, which contrasts with the rather sad character of the original model. The choice of this model is linked to the idea that the child will triumph over death, but also to the Roman taste for Hellenistic models.

Subsequent copies

After the rediscovery of the Farnese Hercules, copies appeared in gardens throughout Europe from the 16th to the 18th century.

During the construction of the Alameda de Hércules (1574) in Seville, the oldest public garden preserved in Europe, two columns from a Roman temple were installed at its entrance, elements of a building still preserved in the Mármoles, an unmistakable sign of admiration for Roman archaeological sites.

On them were placed two sculptures by Diego de Pesquera from 1574, recognizing Hercules as founder of the city, and Julius Caesar, restorer of Híspalis. The former was a copy of the Farnese Hercules, almost the monumental size of the original.

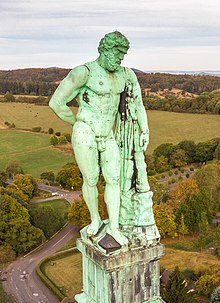

In the Wilhelmshöhe Park near Kassel (Hesse), a colossal 8.5-meter-high version by Johann Jacob Anthoni, 1713-1717, has become a symbol for the city. It stands on an octagonal stone building ("Oktagon") overlooking the park, one of the most important in the city. The building-statue ensemble reaches 69 meters in height: it is the second tallest in the world after the Statue of Liberty in New York.

André Le Nôtre placed a life-size golden version against the skyline at the end of the main view of the Château de Vaux-le-Vicomte. The one in the gardens of the Palace of Versailles is a marble copy by Jean Cornu (1684-1686).

In Scotland, a rare lead copy from the first half of the eighteenth century is incongruously located in the Highlands, overlooking the recently restored Hercules garden in the grounds of Blair Castle. Wealthy collectors could afford one of the many bronze replicas created in tabletop sizes.

A marble copy was made by Giovanni Comino in Rome from 1670 to 1672 and installed in the park of Sceaux in 1686, then in the Tuileries garden from 1793 to 2010, it then returned to Sceaux, with a cast remaining in the Tuileries.

A copy of the Farnese Hercules can be found in Palermo, in the Parco della Favorita, placed on a column in the center of the Fountain of Hercules from which the homonymous avenue leads from the city to the Chinese Palace, the summer residence of the kings of Naples.

A replica, entitled Herakles in Ithaca, was erected in 1989 on the campus of Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. The statue was a gift from its sculptor, Jason Seley, a professor of fine arts. Seley made the sculpture in 1981 from chrome automobile bumpers.

The statue inspired artists such as Jeff Koons and Matthew Darbyshire to create their own versions, in plaster and polystyrene respectively. Their use of white materials to recreate the sculpture has been interpreted by Aimee Hinds as a continuation of colorism in classical art.

Farnese Hercules Posterity

It is shown in the 1954 film Journey to Italy with the Farnese Bull.

A plaster cast is exposed in the station "Museo" of the line 1 of the metro of Naples.

Farnese Hercules in 3D puzzle

In 2012, with the aim of promoting the cultural merchandising of several Italian museums with projects in recycled paper, it is created the puzzle of the Farnese Hercules. Designed by the designer Giacomo Sanna, this puzzle is composed of 300 pieces of cardboard with a thickness of 3 mm each, to be assembled according to a progressive numbering. Copies should be available at the museum bookshop.