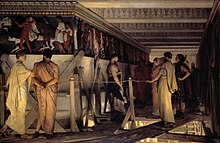

The Parthenon frieze is a 160 meter long frieze that surrounded the upper part of the Parthenon cella in Athens. A masterpiece of classical Greek sculpture, it is made in bas-relief with Pentelic marble in Ionic style, although in a Doric building.

It probably represents the procession of the Great Panathenaeas, which took place every four years in honor of the goddess Athena.

It was sculpted approximately between 443 and 438 B.C. most likely under the direction of Phidias. Some 128 meters of the original frieze survive, about 94%, the rest being known only from drawings made by the Flemish artist Jacques Carrey in 1674. Its fragments are scattered in various museums, notably the Acropolis Museum in Athens and the British Museum in London.

At present, 37.5% of the frieze is in the British Museum; the rest (48%) is in the Acropolis Museum in Athens and the last 14% is divided among other museums. The Greek State has repeatedly requested the restitution of the Elgin Marbles held in London, as well as other elements of the sculpture that decorated the Parthenon.

Much of the Athenian material is not on display, and fragments are in nine other international museums. Molds of the frieze can be found in the Beazley archive at the Ashmolean Museum, Oxford; in the Skulpturhalle, Basel; in the Architecture Hall at the University of Washington, Seattle; and in Hammerwood Park near East Grinstead, Sussex, England.

Construction of Parthenon Frieze

Plutarch's "Life of Pericles," 13.4-9, reports that "the man who directed all the projects and was overseer [episkopos] for him [Pericles] was Phidias.... Almost everything was under his supervision, and, as we have said, he was in charge, because of his friendship with Pericles, of all the other artists."

It should be emphasized that the description was not architekton, the term usually given to the creative influence behind an architectural project, but episkopos. But it is because of this and the circumstantial evidence of Phidias' known work on the Athena Parthenos and his central role in Pericles' building program that his authorship of the frieze is usually inferred.

The marble was quarried from Mount Pentelicus and transported 19 km to the acropolis of Athens. A persistent question has been whether it was sculpted in situ. Just below the molding and above it is a seventeen-millimeter-high channel that may have served to provide access for the sculptor's chisel when finishing the heads or feet of the relief; this guide strip is the best evidence we have that the blocks were sculpted on the wall.

Moreover, from a practical point of view, it is easier to move a sculptor than a sculpture, and to place them by means of a lever in the corresponding place could splinter the edges.

No information has been recovered about the number of people who might have been part of the workshop, with estimates ranging from three to eighty sculptors based on the style, however Jenifer Neils suggests nine, on the basis that this is the minimum number needed to produce the work in the agreed time. It was finished with metal details and painted, with no color surviving, so it must be argued by analogy.

The background may have been blue judging by comparison with funerary stelae and the remains of paint on the Hephaistion frieze. It is possible that the figures held objects that were also represented as the trident of Poseidon and the laurel in the hand of Apollo. The many holes found in the heads of Apollo and Hera indicate that these gods would have been crowned with a crown of gilded bronze. Also, on some occasions it was of gold and silver.

Parthenon Frieze's Dimensions

The frieze is formed by 378 figures, 245 animals; it is 160 meters long, 1 meter high and protrudes 5.6 cm in the places of maximum depth. It is composed of 114 blocks of variable length, 1.22 meters high and 60 centimeters wide, representing two parallel rows in procession. It was a particular novelty of the Parthenon that the cella had an Ionic frieze on the hexastyle pronaos rather than Doric metopes that might be expected of a Doric temple.

Judging from the existence of regulae and drops under the frieze on the east-facing wall, this was an innovation introduced later in the building process and replaced the ten metopes and triglyphs that would otherwise have been placed on the site. It is sculpted in bas-relief, unlike the pediments, in which the figures are in round bulk, and the metopes, which are in high relief.

The system of numbering the frieze blocks was initiated from Adolf Michaelis' (1871) Der Parthenon, since when Ian Jenkins has revised this scheme in the light of recent discoveries.

The convention, here retained, is that the blocks are numbered in Roman numerals and the figures in Arabic numerals, the figures being numbered from left to right against the direction of the procession in the north and west and in favor of it in the south.

Parthenon Frieze's Theme

The scene can be considered as follows: led by the magistrates, a procession advances with knights and soldiers in arms, citizens, musicians, as well as offertory bearers followed by sacrificial animals. The procession heads towards the Acropolis and the assembly of the gods. Citizens and women participate in the procession, accompanied by metecos and representatives of the allies of Athens.

The march of the procession is located on the west side of the temple. The procession is divided into two groups, one heading towards the north side, and the other towards the south side. The two groups join together at the entrance on the east side, under the gaze of the gods who observe the procession.

Description of Parthenon Frieze

The frieze narrative begins in the southwest corner where the procession appears to split into two separate rows. The first third of the western frieze is not part of the procession but instead appears to depict the preparatory stages for the participants.

The first figure here is a strategist (general) dressing, W530, followed by several men preparing the horses W28-23 up to figure W22 who, it has been suggested, may be engaged in the dokimasia, the testing or enlistment of the horsemen (hippeis). W24 is an ambiguous figure who could be the owner of a rejected horse, protesting, or a cerice whose hand held part of a lost salpinx (trumpet), either way this point marks the beginning of the procession itself.

The following rows W21-1 along with N775-136 and S81-61 are all of knights and constitute 46% of the frieze in total. They are divided into two lines of ten rows - significantly, the same number as the Attic tribes.

All are hairless youths -efebos - with the exception of two, W8 and W15, who along with S2-7 wear Thracian garments with fur cap, a patterned cloak and high boots; these have been identified by Martin Robertson as Hipparchs. Then there are four-horse chariots, each with its driver and an armed passenger; there are ten in the southern frieze and eleven in the northern.

Since these passengers are sometimes depicted dismounting they may have represented the apobatids, participants in a ceremonial race from Attica and Boeotia.

By N42 and S89 the equestrian parade has ended and the next sixteen figures in the north and eighteen in the south are considered to be the elders of Athens, judging from their braided hair, an attribute of distinguished age in classical art.

Four of these figures raise their right hand in a clenched fist gesture suggesting a posture related to the olive branch-bearing elders (the thallophoroi/thallophoros) who were elderly men chosen for their good looks in competition. However, they have no holes drilled to insert any branches in their hands. Next in line (N107-114, N20-28) are the musicians: four kithara (or great lyre) players and four aulos (oboe) players.

N16-19 and S115-118 (conjecture) are the hydria bearers (hydriaforoi/hydriaphores), here men rather than Metetian girls mentioned in the literature on the Panathenaeas.

N13-15, S119-121 are the skafeforoi, the tray bearers of the honeycombs and cakes used to lure the sacrificial animals to the altar. N1-12, S122-149 are the ten cows in the south and four cows and four sheep in the north, to be sacrificed on the Acropolis, presumably a shortened form of the hecatomb usually offered on this occasion. It is striking that here there is an a-b-a rhythm of placid and impatient cows.

The frieze narrative begins in the southwest corner where the procession appears to split into two separate rows. The first third of the western frieze is not part of the procession but instead appears to depict the preparatory stages for the participants.

The first figure here is a strategist (general) dressing, W530, followed by several men preparing the horses W28-23 up to figure W22 who, it has been suggested, may be engaged in the dokimasia, the testing or enlistment of the horsemen (hippeis).

W24 is an ambiguous figure who could be the owner of a rejected horse, protesting, or a cerice whose hand held part of a lost salpinx (trumpet), either way this point marks the beginning of the procession itself.

The following rows W21-1 along with N75-136 and S 1-61 are all of knights and constitute 46% of the frieze in total. They are divided into two lines of ten rows - significantly, the same number as the Attic tribes. All are hairless youths -efebos - with the exception of two, W8 and W15, who along with S2-7 wear Thracian garments with fur cap, a patterned cloak and high boots;

these have been identified by Martin Robertson as Hipparchs. Then there are four-horse chariots, each with its driver and an armed passenger; there are ten in the southern frieze and eleven in the northern. Since these passengers are sometimes depicted dismounting they may have represented the apobatids, participants in a ceremonial race from Attica and Boeotia.

By N42 and S89 the equestrian parade has ended and the next sixteen figures in the north and eighteen in the south are considered to be the elders of Athens, judging from their braided hair, an attribute of distinguished age in classical art.

Four of these figures raise their right hand in a clenched fist gesture suggesting a posture related to the olive branch-bearing elders (the thallophoroi/thallophoros) who were elderly men chosen for their good looks in competition.

However, they have no holes drilled to insert any branches in their hands. Next in line (N10-114, N20-28) are the musicians: four kithara (or great lyre) players and four aulos (oboe) players. N16-19 and S115-118 (conjecture) are the hydria bearers (hydriaforoi/hydriaphores), here men rather than Metetian girls mentioned in the literature on the Panathenaeas.

N13-15, S119-121 are the skafeforoi, the tray bearers of the honeycombs and cakes used to lure the sacrificial animals to the altar. N1-12, S122-149 are the ten cows in the south and four cows and four sheep in the north, to be sacrificed on the Acropolis, presumably a shortened form of the hecatomb usually offered on this occasion. It is striking that here there is an a-b-a rhythm of placid and impatient cows.

As the rows converge on the eastern frieze we find the first female celebrants E2-27, E50-51, E53-63. They carry sacrificial instruments and paraphernalia, including phialas (jugs), enochos (wine jugs), thymiaterium (incense burner), and in the case of E50-51 it is evident that they have just given the strategos E49 a káneon (basket), making the girl a canephora.

The next groups E18-23, E43-46, are very problematic. Six on the left and four on the right, if one does not count the other two figures who may or may not be strategos, then this group could be considered to be the ten eponymous heroes who gave their names to the ten tribes.

Certainly their proximity to the gods indicates their importance, but selecting differently then nine of them could be the archons of the polis or atlotetas, magistrates who led the procession; the iconographic evidence is insufficient to determine which interpretation is correct.

The twelve seated gods are considered to be the Olympians, being one-third taller than any other figure in the frieze and are placed in two groups of six on diphroi (backless) stools with the exception of Zeus, who is enthroned. Their backs are turned towards what must be the culminating event of the procession E31-35;

five figures (three children and two adults, and although badly corroded, the two boys on the left are possibly girls) girls carry objects on their heads while a third, possibly a boy, helping an adult who may be the archon Basileus, to fold a piece of cloth. This is usually understood as the representation of Athena's peplo by the arrephorae.

Parthenon Frieze's Style

The Parthenon frieze is the definitive monument of the high classical style of Attic sculpture. It stands between the gradual eclipse of the severe style as can be seen in the metopes of the Parthenon and the evolution of the rich late classical style exemplified by the balustrade of Nike.

From what sources the designer of the frieze drank is difficult to judge. Certainly, large-scale narrative art was familiar to fifth-century Athenians as in the painting of the Stoa Pecile of Polignotus, but without evidence to the contrary it is reasonable to assume that the novelties of the Parthenon belong exclusively to Phidias and his workshop.

This period is one of discovery of the expressive possibilities of the human body; there is a greater freedom in postures and gestures, and a growing attention to anatomical verisimilitude that can be seen in the weighted postures of figures W9 and W4 that partially anticipate Polyclitus' Doriphorus.

There is a remarkable comfort in the physiques of the frieze compared to the rigidity of the metopes along with an eye for subtleties such as knuckle tendons, veins and careful articulation of musculature.

An important innovation of the style is the use of drapery as an expression of movement or to suggest the body underneath; in archaic and early classical sculpture, clothing fell over the body as if it were a curtain obscuring the form beneath it, now we find the undulating chlamys of knights or the many folded peplums of women that allow for surface movement and tension in their otherwise static poses.

The variation in the horses' manes has been of particular interest to scholars attempting to discern the artistic personalities of the sculptors who worked on the frieze, so far this Morellian analysis has been inconclusive.

Interpretation of Parthenon Frieze

As no description of the frieze has survived from antiquity the question of the sculpture's meaning has been persistent and still unresolved. The first published attempt to interpret it belongs to Cyril of Ancona in the 15th century who referred to it as the "victories of Athens in the time of Pericles. "

However, what is today the orthodox view of the piece, namely, that it represents the procession of the Great Panathenaeas from Eleusis to Athens, was weighed by Stuart and Revett in the second volume of their The Antiquities of Athens, 1787.

Subsequent interpretations have built extensively on this theory even if they reject that a sculpture in a temple can represent a contemporary rather than a mythological or historical event. Only in recent years has an alternative thesis been developed, and that is that the frieze represents the founding myth of the city of Athens rather than the festival.

The idea that the scene is a document of the feast of Athena is fraught with problems. It is known from late sources that a number of classes of individuals who played a role in the procession are not present in the frieze, such as the hoplites, the allies of the League of Delos, the skiaforoi or umbrella-bearers, the female hydraiforoi (there are only male hydria-bearers), thetes, slaves, metecos, the panathenaic ship, and some would suggest the canephoras.

That what we see today was intended as a generic image of the religious festival is problematic as no other sculpture in a temple depicts a contemporary event involving mortals. So locating the scene in mythical or historical times has been the main difficulty in this line of research.

John Boardman has suggested that the cavalry represents the heroization of the Marathonomachoi, the hoplites who fell at Marathon in 490, and that therefore these horsemen would be the Athenians who intervened in the last Great Panathenaeans prior to the war.

In support, he points out, the number of horsemen, chariot passengers (but not drivers), grooms and marshals come to be the same number as those that Herodotus gives for the Athenian dead: 192. Equally suggestive of a reference to the War with Persia is the similarity that several scholars have found with the frieze of the Apadana sculpture at Persepolis.

Differently, it would be the Athenian democrats depicting themselves as opponents of an Eastern tyranny: aristocratic Athens emulating the Imperial East. Furthering this "spirit of an age" argument we have JJ Politt's who sees the frieze as embodying the manifesto of Pericles, which favored the cultural institutions of agones (or contests, as witnessed by the apobatai), sacrifices, and military training as well as a host of other democratic virtues.

Recent studies along the same lines have made the frieze a site of ideological tension between the elite and the demos with perhaps only the aristocracy present and a thinly veiled reference to the ten tribes.

The pediments, metopes and shield of Athena illustrate the mythological past and as the gods are observing in the eastern frieze it is natural to look for a mythological explanation. Chrysoula Kardara has ventured that the relief shows us the first Panathenaean procession instituted under the mythical king Cecrope.

This would certainly explain the absence of the allies and the boat as these are later than the original practice of the sacrificial rite. This author points to E35 as the future king Ericthonius presenting the first peplo to his predecessor Cecrope, iconographically similar to the depiction of the boy on a fragmentary kylyx from 450 BC. (Acropolis 396).

A recent, more radical interpretation, by Joan Breton Connelly, identifies the central scene in the eastern frieze (thus above the cella door and focal point of the procession) not as the giving of Athena's peplum by the Arrephorae, but the donation of the sacrificial garment by the daughter of King Erechtheus in preparation for the sacrifice of her life.

An interpretation suggested by the text of the fragmentary papyrus remains of Euripides' Erechtheus, where his life is demanded to save the city of Eumolpus and the Eleusinians. Thus the gods turn their backs on him to avoid the contamination of the vision of his death.

Influence in Parthenon Frieze

The oldest surviving works of art that show traces of the influence of the Parthenon frieze belong to the media of painting on vases and engraved stelae where one can find a certain echo not only of motifs, themes, postures but also the tenor of the same. Direct imitation, and certainly quotation, of the frieze begins to be pronounced around 430 B.C.

A striking example, an explicit copy, is a pelike attributed to the wedding painter (Berlin F 2357) of a young man "parking" the horse in exactly the same way as the figure W25 of the frieze. While those paintings on pottery that resemble the frieze are concentrated around 430, the vessels that cite the pediments are dated closer to the end of the century providing further evidence of the priority of the sculptural program.

More talented painters also found inspiration in sculpture, notably Polyignotus I and his group, especially the painter Peleus, the painter Cleophon, and the late work of the painter of Achilles.

Later talented painters also managed to capture the mood of eusebeia or pensive piety of the procession as, for example, in Cleophon's scrolled krater of a sacrifice to Apollo (Ferrara T57), which shares the quiet dignity of the best sculpture of high classicism.

It is natural to look for resonances of the frieze in late 5th century BC Attic relief sculpture; these can be discovered to some extent in the public works of the Hephaestion frieze and the balustrade of the Athena Nike, where the imagery of the seated gods and the sandal-binder respectively probably owe a debt to the Parthenon.

Traces can likewise be found in private commissions for funerary stelae of the period, for example the "cat stele" from Aegina (NAMA 715) shows a clear similarity to figures N135-6. The same is true of the Hermes of the four-figure relief known from a Roman copy (Louvre MA 854).

Later Hellenistic and Roman Classicist art also looked to the frieze for inspiration as can be seen in the Lycian sarcophagus of Sidon, (Phoenicia), the Ara Pacis Augustae, the Gemma Augustea, and many pieces from the generation of the Roman emperor Hadrian.