The Venus de Milo is a statue from Ancient Greece belonging to the collection of the Louvre Museum, located in Paris, France.

The story of its discovery in 1820 on the island of Milo, then part of the Ottoman Empire, and the way it lost its arms were told by early sources in contradictory versions that could never be clarified at all, but after its acquisition by France it was immediately exhibited in the Louvre, officially as a masterpiece of the prestigious classical generation and attributed to the circle of Praxiteles, becoming an instant celebrity and a source of nationalistic pride.

But a controversy soon arose, because according to some scholars there was evidence to believe that it had in fact been produced in the Hellenistic period, at the time despised as a decadent phase in the Greek artistic tradition, and this possibility was of no political interest to the French government.

The debate went on for a long time, but even so its aesthetic value was not seriously doubted, and it was praised in high terms by many artists and intellectuals, and even by the lay public. It was copied many times and disseminated in prints and other widely circulated media throughout the 19th century.

Like few works of antiquity, the Venus de Milo survived relatively unscathed by Romantic and Modernist criticism, seeing its fame grow steadily. It has been the subject of many specialized studies and has acquired the status of a popular icon, reproduced countless times as a statue, in prints, films, literature, tourist souvenirs, and other items for mass consumption.

It is today one of the best known ancient statues in the world. Its authorship and dating remain controversial, but a consensus has formed that it is actually a Hellenistic work that nevertheless recovers classical elements, attributed to Alexander of Antioch. Although it is modernly described as a representation of Venus, goddess of beauty and love, neither is this identification absolutely certain.

Venus de Milo's Description

The work, 2.02 m high, is basically composed of two large segments of Paros marble, with several other smaller parts worked separately and connected to each other by iron clamps, a technique common among the ancient Greeks. The goddess wore metal jewelry - armband, earrings, and tiara - presumed by the existence of fixing holes. She may have had other adornments, and her surface may have received paint, which however left no traces.

The figure stands erect and remains naked up to the hip, while the lower limbs are hidden under a richly pleated cloak that exploits light and shadow effects. Her left leg is elevated, slightly bent and projected forward, while her weight rests on her right leg, causing a slight curvature in her torso.

His hair, long and wavy, is parted in half and gathered behind to form a bun. Her face, whose smooth features have been much admired, sketches a slight smile. She is missing both arms and her left foot. Her finish is uneven, being more refined on the front than the back, a common practice when statues were to be installed in niches, as she was.

Discovery of Venus de Milo

The story of its discovery and acquisition is unclear, and many versions have circulated that disagree on several important details, so much so that it has been said ironically that more ink has been spent trying to elucidate this controversy than blood has been shed for Helen of Troy.

According to Marianne Hamiaux, the sculpture was unearthed on April 8, 1820 by the peasant Yorgos Kentrotas near the ancient city on the island of Milo (also known as Milos or Melos) in the Aegean Sea, then part of the Ottoman Empire. Kentrotas was looking for stones to build a wall around his camp. By chance, a French naval cadet, Olivier Voutier, was with him. Fond of archaeology, Voutier encouraged Kentrotas to continue digging, as he left the record:

"A peasant was removing stones from the ruins of a buried chapel. Seeing him stop and look at the bottom of the hole, I went to him. He had dug up the top of a statue in very good condition. I offered him payment to continue digging. And indeed, he soon found the lower part, but it did not fit the other. After searching more carefully, he found the center piece."

Louis Brest, vice-consul of France in Milo, alerted to the find, caused the excavations to proceed, and more fragments emerged, among them a hand holding an apple, three blocks with inscriptions, and two pillars of hermas. In between, Brest referred the discovery to two other visiting officials, Jules Dumont d'Urville and Lieutenant Matterer, who also saw the statue in situ. D'Urville also left an account:

"The statue was in two pieces, firmly held together by iron clamps. The Greek peasant, fearful of losing the fruit of his labor, had hidden the upper half in a stable, together with two statues of Hermes.

The other half was still in its niche. I measured the two parts separately; the statue is approximately six feet high; it is a representation of a naked woman holding an apple in her raised left hand, while her right hand holds her carefully draped robes, which fall from her hips to her feet; both arms were damaged and, in fact, were detached from her body.

The only visible foot is bare; the ears are pierced and must have been adorned with earrings. All these features suggest that the image is of Venus at the trial of Paris; but in this case, where will Juno, Minerva, and the beautiful shepherd be?"

Voutier pressed the consul for the French government to buy the statue, but as negotiations were delayed, Kentrotas offered it to a local priest, who in turn intended to gift it to a Turkish potentate. D'Urville informed Charles François de Riffardeau, Marquis de Rivière and French ambassador to the Sublime Porte, who sent an embassy secretary, Viscount Charles de Marcellus, an experienced antiquarian, to the island to secure possession of the gem for France.

Marcellus arrived in the port of Milo just as the statue was being loaded onto a ship bound for Constantinople to be delivered to the Turk. After delicate negotiations, it was purchased on behalf of the Marquis de Rivière.

Venus was then boarded the French ship and proceeded to Constantinople, where she was handed over to Rivière and kept hidden from Turkish officials. Rivière had coincidentally been called to a new position in Paris, taking her with him, not without passing through Milo again to ascertain if there were no other relics for sale.

Arriving in Marseille on December 1, 1820, he delivered the cargo to the envoy of the Royal Museums, who shipped it to Paris along with other fragments. In 1821 Rivière finally offered it to King Louis XVIII, who then donated it to the Louvre Museum.

Venus de Milo's Identification

Several scholars addressed the problem of its identity, but influences from the political context of the time had a bearing on this question. France had been forced to return several relics of antiquity that Napoleon Bonaparte had confiscated in his campaigns of conquest throughout Europe, and so the acquisition of the Venus immediately focused all official attention.

It was necessary to reaffirm its artistic value, to compensate for the forced return of such gems as the Apollo Belvedere, the Venus de Medici, and the Laocoon Group, and to compete with England, which had recently acquired the monumental Elgin Marbles by Phidias. A consensus was formed that the piece was a great masterpiece, but the determination of its origin actually proved problematic and, in part, disappointing.

The very incompleteness of the statue opened the way for numerous conjectures regarding its original posture and the action in which it would be engaged, which could identify the episode in the myth that the composition illustrates, making clear the significance of the work.

Quatremère de Quincy, permanent secretary of the Institute of Fine Arts, rejected the hand with the apple as having a rough finish and incompatible with the rest, and saw the goddess as a Venus Victrix (Victorious Venus), attributing its authorship to the circle of Praxitheles, dating it to the mid-fourth century BC, but Éméric-David, an eminent art historian,

accepted the hand, identifying it as the Venus of the beauty contest judged by Paris, and considered a slightly older origin, placing it as an intermediate between the schools of Phidias and Praxytles. Count Frédéric de Clarac, Curator of Antiquities at the Louvre, for his part, accepted that one of the inscribed blocks that had been found with her in fact belonged to the statue.

The inscription read, "-ανδρος Μηνίδου / [Ἀντ]ιοχεὑς ἀπὸ Μαιάνδρου / ἐποίησεν," meaning "(Alex)-andros (or Ages-andros), son of Memides, from Antioch in the Meander, made this statue." Alexander was a completely unknown name, and Antioch at the Meander being a city founded in 281 BC, if the block really was of Venus, this would define a Hellenistic origin, a school then considered decadent, and put to rest any hope that the work was a product of the most prestigious Greek sculptors, those of the classical period.

Taking into account the style of the letters used in the inscription, its dating would be between 150-50 B.C. Count Louis de Forbin, director of the Louvre, frustrated with this result, claimed that the block was a late addition and not part of the original set, deciding that it did not need to be reinstated.

This fragment has since disappeared without a trace, and its existence only became known outside official circles because the painter Jacques-Louis David, knowing of the acquisition, sent one of his students, Auguste Debay, to make a drawing of the work, which has survived.

At first the idea of the museum's chief conservator, Bernard Lange, was to restore the work in its entirety, recreating all the missing parts, a common practice at the time, but since the position of the arms could not be determined with certainty, it was decided to make only a slight restoration at the tip of the nose, the lower lip, the big toe of the right foot, and some folds of the cloak, also adding the left foot and a rectangular base to support it.

In May 1821 the museum officially announced the exhibition of the Venus de Milo as a product of Praxiteles' school, in a statement that had the endorsement of Quatremère, persuaded by Forbin to authenticate the work.

It was not long before Clarac, who had defended its Hellenistic origin and had therefore been excluded from the decisions, raised a public controversy about the identification of the statue, saying that the restoration had been done hastily and clandestinely.

On the cover of the pamphlet he circulated was the drawing of David's pupil. It turned out that Clarac's reputation as a scholar was not very solid in France, but his arguments were quickly accepted by the Germans, creating an international debate.

In addition to Clarac, Charles Lenormant, Adolf Furtwängler and other 19th-century experts denounced the disappearance of the block as the convenient result of the political desire to eliminate proof of Hellenistic authorship.

Discussions about its origin only subsided when Furtwängler published his influential collection of essays Meisterwerke der Griechischen Plastik in 1893, devoting a chapter to Venus and attributing it to the Hellenistic school on the basis of the inscription, although in judging its aesthetic value it proved to be influenced by the prejudices that still hung over the period.

Today there is a consensus that the work is indeed a Hellenistic creation based on its style characteristics, and although some doubts still remain, several prominent authors accept that the famous missing block was indeed part of the work, reinforcing the consensus, such as Brunilde Ridgway, Jerome Pollitt, Fred Kleiner and Ian Chilvers, editor of the Oxford Dictionary of Art.

As is typical of the art of Hellenism, the Venus de Milo is a stylistically eclectic work, as artists of the period enjoyed recovering, in new combinations, elements of older styles as a sign of erudition and as proof of technical mastery. Ivan Zoltovskij identified that his proportions follow the golden section, a classical canon par excellence, while Hellenistic works usually have more elongated forms.

The impassive air of his countenance and the harmony of his facial features are common to the 5th century BC of so-called High Classicism, while the style of the hairstyle and the delicate shaping of the body point to the 4th century BCE, of Low Classicism. Her general posture with a spiral movement, the small breasts and the pattern of the folds of her robe, on the other hand, agree with the formal innovations introduced by Hellenistic sculptors.

This does not prevent that the statue could alternatively be a Hellenistic retelling of a lost classical original. It seems to belong to a definite iconographic family, composed of works such as the Winged Victory of Brescia and the Venus of Capua. Some of them have the complete limbs, which may also suggest the original configuration of the Venus de Milo.

These similarities seem to support the idea of a classical descent, possibly being a Venus Victrix, which would be reflected in the shield of Mars, which she would carry between her hands, symbolizing the cessation of war through love. Her left foot would perhaps be wearing a trophy of arms, or a helmet. It has also been suggested that she could be a derivation of the Venus of Capua or the Venus of Cnidus of Praxitheles.

The Louvre Museum, where she is found, declines to indicate a definite authorship and identifies her as a Hellenistic creation of the late 2nd century B.C. Her author may have been connected with the school of Rhodes or that of Pergamos.

Nor could the identity of the goddess be established with certainty. Although there are good arguments in favor of Venus and this identification has crystallized, it has also been suggested that it may be Amphitrite, a deity venerated at Milo, or Diana or a Danaid. The niche where she was found is now recognized as part of an ancient gymnasium.

Above the niche was another inscription, which likewise was lost but has been preserved in a design, celebrating the dedication of the building to Hermes and Hercules, traditional patrons of athletes. The herms found with Venus corroborate this identification of the site, and the presence of an image of Venus in this context was not uncommon, as literary sources attest.

Venus de Milo's The arms

The question of the missing arms is equally confusing. There survives an anonymous drawing of the work in Kentrotas' stable showing it intact, Voutier made another visual record and showed it separated into two parts without the arms, and D'Urville said that the arms were separate from the body, though clearly part of the whole.

One version of the story derived from Marcellus' account says that the priest would have been ordered to return the relic, but, refusing to do so, the French would have resorted to the use of force, eventually breaking his limbs. Concerned with getting out of there right away, once the statue was captured, they would not have turned back to retrieve the lost fragments. Marcellus, however, is not currently considered at all reliable.

On the other hand, Matterer said that the arms found did not belong to him. He later retracted this statement, saying, "When I saw the statue.... the left arm was joined to the torso and (the hand) held an apple above the level of the head."

In any case, by the time it arrived in Paris it was mutilated, but other fragments followed with it, including the hand with the apple and part of the left arm. Lange, the Conservator of the Louvre, stated that certain patterns in the abrasions suffered by Venus, which ran down the left shoulder and repeated in the same direction on the back of the hand, indicated that this fragment was originally part of the work.

Many years later, when Adolphe Thiers assumed the presidency of France, he commissioned his ambassador to Greece, Jules Ferry, to travel to Milo in order to gather local lore about the statue.

Ferry managed to locate Kentrotas' son and nephew, who described in detail the posture of the Venus, saying that she when found still had both arms. The Louvre currently states that the controversial original arms were never found, but the other unrestored fragments, whose belonging to the statue is disputed, are preserved separately in the same museum.

Movements and restoration of Venus de Milo

On permanent display in a special room in the Sully Wing of the Louvre Museum, where it is visited by crowds, the Venus rarely left its home. In 1862 it was taken to London to be prominently exhibited in the Crystal Palace, with great public success.

During the Franco-Prussian War (1870-1871), fearing looting and vandalism, the then Curator of Sculptures at the Louvre, Félix Ravaisson, hid it in a police station, along with documents, behind a wall, which was sealed and disguised as old masonry.

After the war the Venus was removed from its hiding place, but it was found that the joint of the two parts of the torso had been damaged, with the important effect of altering the figure's posture. Only in 1883 was its original position recomposed, taking advantage of removing part of Bernard Lange's restorations.

During the two world wars the statue was removed from the museum and hidden for security reasons, and in 1964 the French government sent it to Japan on the occasion of the Olympic Games as "Ambassador of Greece", part of a cultural outreach project that, according to Herman Lebovics, also had a political statement intention.

On transport the statue again suffered damage to its fittings, being restored in Japan by Louvre experts, and has not been removed from the museum since.

Between 2009 and 2010 it underwent further restorative interventions. It was cleaned of the dust that had accumulated and Lange's plaster additions that still concealed minor surface damage and the cracks between the marble pieces it is made of were removed.

But it was decided to keep some of the old expert's restorations that still remained, such as the nose, in order to retain the look for which she became best known.

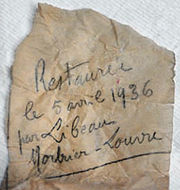

During the work, it was discovered that she had undergone one restoration in antiquity and another in the 20th century, this one not officially documented, but attested to by a note found in a crevice near her right breast and hidden by plaster, which read, "Restored on April 5, 1936 by Libeau, marble maker - Louvre."

Venus de Milo's Fame

The fame of the Venus in antiquity is not known, but the occurrence of other specimens with some variations in her typology indicates that the basic model was popular. She presents on her surface numerous mutilations that were apparently caused by violent blows, and Carus supposes that after the rise of Christianity she must have been the object of the fury of a mob that tried to destroy the pagan idol.

Since it was exposed again, with the help of French government propaganda the statue immediately became notorious, obscuring the Venus de' Medici, until then the most esteemed female representation of antiquity. It was copied several times and specialized studies began to appear.

During Romanticism it was one of the few works from Antiquity that escaped negative criticism, but it seems that she did not come to supplant the fame of other works by male subjects, even though she continued to be studied assiduously by young sculptors.

But for the classicists it became a workhorse, and artists such as Leconte de Lisle and Pierre Puvis de Chavannes wrote praise or took it as a subject for re-readings. By the mid-19th century she was already a true popular icon, her fame acquired international contours, and she became an ideal object of male desire.

Walter Pater, writing at this time, was one of the first to extol her incompleteness as part of her expressive power, and according to Elizabeth Prettejohn the Venus contributed significantly to the formation of the modern taste for the fragment and for time-worn works.

To the English she became as esteemed as the Elgin Marbles. Samuel Phillips declared her to be the most perfect combination of majesty and beauty in female form, Nathaniel Hawthorne praised her as "one of those lights that shine on a man's path," and a plaster copy was acquired by the British Museum for the express purpose of serving as a model for art students.

The painter James Whistler kept a copy in his studio all his life to remind him of the ideal female forms as he worked with a live model. By the 1870s the corset fad was flourishing, but for critics of this apparatus of female beauty, it caused deformity in women's bodies, and Venus was regularly cited as a model of natural beauty.

She saw her popularity increase, being particularly revered by symbolists as the embodiment of celestial beauty, but also beginning to be the subject of jokes and subversive interpretations of her status as a cultural icon.

Shortly afterwards exponents of modernism, such as Salvador Dalí, René Magritte, and Marcel Duchamp, created re-readings of the statue, and others at the time saw it as "an unnecessary baggage for modernity," as Malevich described it. Renoir despised it saying it looked like "a great gendarme."

Regardless of the criticism, her presence grew larger; her profile became an ideal for female physical education, her pose inspired actresses in theaters and models in pornographic photographs, and her image was associated with the advertising of numerous commercial products.

Queen Guilhermina of the Netherlands ordered the sculptor Karl Bitter to make a copy of Venus to inspire her at times when she was to make decisions of state, but demanded that his version have arms.

Names of the recent avant-garde such as Yves Klein and Niki de Saint Phalle have also dedicated themselves to Venus in works of rereading, and in this sense, according to Dalia Judovitz, she is one of the most reinterpreted works in history.

Today her figure has a worldwide circulation; it has appeared, in varied approaches, in films, documentaries, novels, poetry, children's magazines, in two- and three-dimensional reproductions of all sizes and in materials from the noblest to the most vulgar, has been the subject of numerous academic studies, and is also a popular tourist souvenir.

Its fortune among the general public and scholars has been exceptionally favorable, second only to that of the Mona Lisa, and the absence of its arms continues to be singled out as a major factor in its fascination.

According to the Oxford Companion to the Body, it is possibly the most celebrated statue in the history of the artistic nude, the Concise Oxford Dictionary of Art and Artists refers to it as the best known of all ancient statues, and Gregory Curtis, writing for Smithsonian Magazine, described it as the second most famous work of art in the entire world, second only to the Mona Lisa.